Mucoromycotina

Timothy Y. James and Kerry O'Donnell

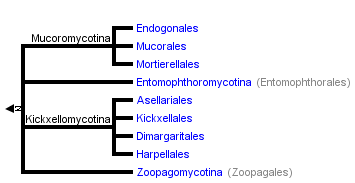

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxThe tree shown above is based on several phylogenetic analyses of gene sequences of nuclear small subunit (SSU) ribosomal DNA (Lutzoni et al. 2004, Nagahama et al. 1995, O'Donnell et al. 1998, Tanabe et al. 2000), elongation factor 1α, the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB1; Tanabe et al. 2004), and combined analysis of multiple genes (James et al. 2006; White et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2006). Most of the clades shown are strongly supported as monophyletic, but relationships among them are poorly resolved. Moreover, monophyly of the Zygomycota remains controversial, and it was not included as a formal taxon in the "AFTOL classification" of Fungi (Hibbett et al., 2007). This page is currently being revised to reflect understanding of the phylogeny of taxa formerly placed in Zygomycota.

Introduction

The Zygomycota contains approximately 1% of the described species of true Fungi (~900 described species; Kirk et al. 2001). The most familiar representatives include the fast-growing molds that we encounter on spoiled strawberries (Figure 1) and other fruits high in sugar content. Although these fungi are common in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, they are rarely noticed by humans because they are of microscopic size. Colonial growth and the taxonomically informative asexual reproductive structures Zygomycota produce are typically studied after culturing on various agar media. Direct microscopic observation of suitable substrates is required for those species that either have not or cannot be cultured. Fewer than half of the species have been cultured and the majority of these are members of the Mucorales, a group that includes some of the fastest growing fungi.

Figure 1. Moldy strawberries covered with Rhizopus mycelium. Photo K. O'Donnell.

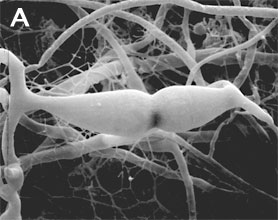

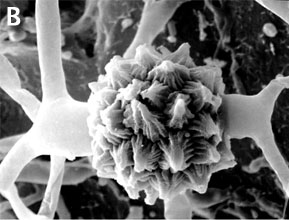

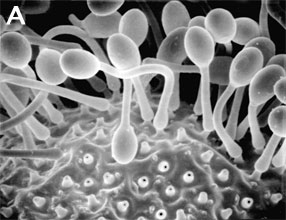

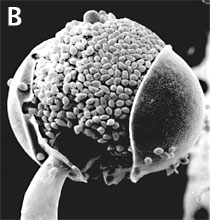

Zygomycota are defined and distinguished from all other fungi by sexual reproduction via zygospores following gametangial fusion (Figure 2A,B) and asexual reproduction by uni-to-multispored sporangia (Figure 3A,B) within which nonmotile, single-celled sporangiospores are produced. The phylum comprises at least seven phylogenetically diverse orders. Monophyly of the phylum and interrelationships among orders are currently under intensive investigation using multilocus DNA sequence data. This introduction to the Zygomycota does not include the order comprising the arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi, the Glomales, because it has been elevated to the rank of phylum, the Glomeromycota (Schüßler et al. 2001). One other group, the Microsporidia, were previously considered protozoa, however, DNA, biochemistry, and morphology suggest these highly reduced, obligate, intracellular parasites may have evolved from a zygomycete-like ancestor (Keeling 2003).

Figure 2. Sexual reproduction. (A) Scanning electron micrograph of gametangial fusion in Mucor mucedo. (B) Highly ornamented zygosporangium of Mycotypha africana. (From O'Donnell 1979).

Figure 3. Asexual reproduction. (A) Scanning electron micrograph of unispored sporangia of Benjaminiella poitrasii and (B) dehisced multispored sporangium of Gilbertella persicaria releasing sporangiospores. (From O'Donnell 1979).

Zygomycota are arguably the most ecologically diverse group of fungi, functioning as saprophytes on substrates such as fruit, soil, and dung (Mucorales), as harmless inhabitants of arthropod guts (Harpellales), as plant mutualists forming ectomycorrhizae (Endogonales), and as pathogens of animals, plants, amoebae, and especially other fungi (all Dimargaritales and some Zoopagales are mycoparasites). A number of species are used in Asian food fermentations, such as Rhizopus oligosporus in the Indonesian staple tempeh, and Actinomucor elegans in Chinese cheese or sufu (Hesseltine 1991).

Conversely, some species have a negative economic impact on human affairs by causing storage rots of fruits (particularly strawberries by Rhizopus stolonifer [Figure 1]), as agents of plant disease (e.g., Choanephora cucurbitarum flower rot of curcurbits), while other species can cause life-threatening opportunistic infections of diabetic, immuno-suppressed, and immuno-compromised patients (de Hoog et al. 2000). In addition to some Mucorales that attack immuno-suppressed humans, several species of microsporidia cause serious human infections. Some zygomycetes are regularly isolated by veterinarians from domesticated animals in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, including the US gulf states.

Characteristics

Zygomycota, like all true fungi, produce cell walls containing chitin. They grow primarily as mycelia, or filaments of long cells called hyphae. Unlike the so-called 'higher fungi' comprising the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota which produce regularly septate mycelia, most Zygomycota form hyphae which are generally coenocytic because they lack cross walls or septa. There are, however, several exceptions and septa may form at irregular intervals throughout the older parts of the mycelium or are regularly spaced in two sister orders of Zygomycota, the Kickxellales and Harpellales.

The unique character (synapomorphy) of the Zygomycota is the zygospore. Zygospores are formed within a zygosporangium after the fusion of specialized hyphae called gametangia during the sexual cycle (Figure 2A). A single zygospore is formed per zygosporangium. Because of this one-to-one relationship, the terms are often used interchangably. The mature zygospore is often thick-walled (Figure 2B), and undergoes an obligatory dormant period before germination. Most Zygomycota are thought to have a zygotic or haplontic life cycle (Figure 4). Thus, the only diploid phase takes place within the zygospore. Nuclei within the zygospore are believed to undergo meiosis during germination, but this has only been demonstrated genetically within the model eukaryote Phycomyces blakesleeanus (Eslava et al. 1975).

Figure 4. Generalized life cycle of Zygomycota. Asexual reproduction occurs primarily by sporangiospores produced by mitosis and cell division. The only diploid (2N) phase in the life cycle is the zygospore, produced through the conjugation of compatible gametangia during the sexual cycle (see Figure 2A, B).

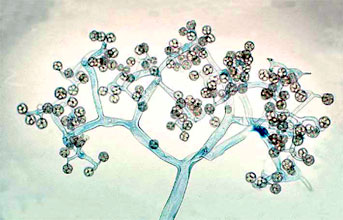

Zygomycota typically undergo prolific asexual reproduction through the formation of sporangia and sporangiospores. Sporangiospores are distinguished from other types of asexual spores, such as conidia of the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, by their development. Walled sporangiospores are formed by the internal cleavage of the sporangial cytoplasm. At maturity, the sporangial wall typically disintegrates or dehisces (Figure 3B), thereby freeing the spores that are usually dispersed by wind or water.

Sporangia are formed at the ends of specialized hyphae called sporangiophores. In the model organism, Phycomyces blakesleeanus, sporangial development has been studied extensively to understand the genetic basis for various trophisms, including the strong phototrophic responses to blue light. A unique spore dispersal strategy for the Mucorales is exhibited by the dung fungus Pilobolus, whose name literally means 'the hat thrower' (see far left Title illustration). The entire black sporangium is explosively shot off of the top of the sporangiophore up to distances of several meters. Phototrophic growth of the sporangiophore facilitates dispersal away from the dung onto a fresh blade of grass where it may be consumed by an herbivore, thereby completing the asexual cycle after the spores pass through the digestive system. Some members of the Entomophthorales (e.g., Basidiobolus, Conidiobolus) also reproduce via forcibly discharged asexual spores. Interestingly, species of Basidiobolus, Conidiobolus and several other genera produce a second kind of spore on a long stalk that appears to have certain morphological adaptations for efficient insect dispersal.

Figure 5. Dichotomously branching sporangiophore of Thamnidium elegans (Mucorales). The few-spored sporangiola are borne at the tips of the sporangiophore branches (© G. L. Barron 2004).

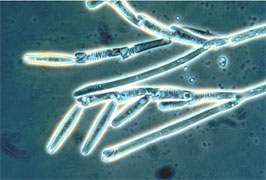

Two variant types of sporangia include sporangiola and merosporangia. Sporangiola are simply uni-to-few spored sporangia containing between 1-to-30 spores (Figures 3A and 5). Merosporangia are elongated sporangiola with uniseriate spores usually produced from a vesicle or stalk (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Scanning electron micrograph of uniseriate merosporangia produced on a vesicle (hidden beneath merosporangia) of Syncephalastrum racemosum (Mucorales). (From O'Donnell 1979).

Merosporangiferous members of the Zygomycota, however, do not form a clade, indicating that this sporangial type has evolved independently more than once within the phylum (e.g., Mucorales and Zoopagales). A unique sporangiolum type is the trichospore, a one-spored sporangiolum, produced by members of the Harpellales (Figure 7 and far right Title slide), which are endocommensals living within the gut of arthropods, including terrestrial beetles and millipedes, fiddler crabs, and the larvae of many aquatic insects (Lichtwardt 1986). Trichospores possess one to several basal hair-like filaments that likely aid in the attachment of the spores to debris and plants in aquatic ecosystems before they reenter the arthropod gut.

Figure 7. Photo of thallus of Genistellospora homothallica (Harpellales) bearing trichospores attached to the hindgut cuticle of a Chilean blackfly. (© Misra and Lichtwardt 2000).

Like other Fungi, Zygomycota are heterotrophic and typically grow inside their food, dissolving the substrate with extracellular enzymes, and taking up nutrients by absorption rather than by phagocytosis, as observed in many protists. The most common members of the Zygomycota are the fast growing members of the Mucorales. They function as decomposers in soil and dung, thereby playing a significant role in the carbon cycle.

Zygomycota also participate in a number of interesting symbioses. As mentioned above, the Harpellales inhabit arthropods (particularly freshwater aquatic insect larvae; Figure 7) where they are attached to the chitinous lining of the hindgut. Harpellids presumably feed on nutrients that are not utilized by the arthropod. Because they are generally assumed to neither harm nor benefit the host animal, this association is considered commensalistic. In contrast, the Entomophthorales include many insect pathogens that can cause huge disease outbreaks (see center Title slide showing infected maggot fly). Some of this pathogenicity is being tapped for use in the biocontrol of specific insect pests, including periodical cicadas (Bidochka et al. 1996; Hajek 1999). A number of other Zygomycota are mycoparasitic, or parasites of other fungi. All members of the Dimargaritales (only 15 species) and many Zoopagales are typically obligate parasites of mucoralean hosts. Other mycoparasites in the Mucorales (e.g., Syzygites, Spinellus) specialize on mushroom fruiting bodies (Basidiomycota; Figure 8).

Figure 8. Sporangia of Spinellus fusiger (Mucorales) parasitic on fruitbodies of the mushroom Mycena pura. (© Malcolm Storey 2004).

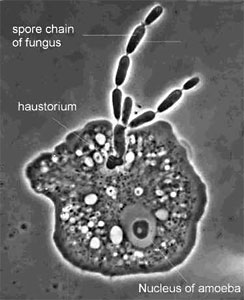

Certain species of Zoopagales parasitize non-fungal hosts, such as nematodes, rotifers, and amoebae (Figure 9). The Endogonales are a unique group in the Zygomycota because some members can form ectomycorrhizal associations with pine roots, while others appear to be saprobic.

Figure 9. The parasite Amoebophilus simplex (Zoopagales) and its amoeba host. Nutrient transfer occurs through a specialized hypha called a haustorium that enters the amoeba. Spores are produced in chains, and they are engulfed by scavenging amoebae to begin the infection process (© G. L. Barron 2004).

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

The Zygomycota are thought to have diverged from the remaining fungi before the colonization of land by plants 600-1,400 million years ago (Berbee and Taylor 2001; Heckman et al. 2001). Molecular phylogenetic studies place the Zygomycota near the base of the kingdom Fungi, diverging after the Chytridiomycota, the most basal fungal lineage (James et al. 2006; White et al. 2006). However, as presently circumscribed, it is uncertain whether the Zygomycota represent a monophyletic group. Studies using SSU rDNA sequence data have generated molecular phylogenies suggesting the Zygomycota may be either para- or polyphyletic (Bruns et al. 1992; Tanabe et al. 2000, 2004). With the recent removal of the Glomales from the Zygomycota (Schüßler et al. 2001), this phylum is restricted to species which form zygospores through mycelial conjugation, at least in those species where sexual reproduction is known.

Prior to the use of molecular phylogenetics, the Zygomycota were classified into two classes, the Zygomycetes and Trichomycetes (Alexopoulos et al. 1996). Analyses of SSU rDNA sequences, however, have shown that the Trichomycetes are polyphyletic, comprising what we now know are Ichthyosporean protozoans related to animals (Benny and O'Donnell 2000; Ustinova et al. 2000) and also some true Fungi, the Harpellales, which are nested within the Zygomycetes (O'Donnell et al. 1998; Tanabe et al. 2000). Although relationships among the orders are poorly understood, analyses of RPB1 DNA sequences resolved a clade comprising the Kickxellales-Harpellales-Dimargaritales (Tanabe et al. 2004). A morphological synapomorphy for this clade is the possession of a uniperforate septum with a lenticular cavity (Figure 10; Benny et al. 2001). A large-scale phylogeny of the Mucorales, using three genes and at least one member of each recognized genus, suggests that several of the largest families and the two largest genera (Mucor and Absidia) are polyphyletic (O'Donnell et al. 2001).

Figure 10. Transmission electron micrograph of vegetative hypha of Kickxella alabastrina (Kickxellales). White line separating the upper from the lower cell is a section of the cross wall or septum. Note the lens shaped plug that lies within the septal pore (lenticular cavity). Scale bar = 0.5 µm. (From Tanabe et al. 2004; © Elsevier 2003).

The Entomophthorales appears to be one of the most distinctive and problematical lineages of Zygomycota for two reasons: 1) SSU rDNA analyses suggest that it may be more closely related to the Blastocladiales (Chytridiomycota) (James et al. 2000; Tanabe et al. 2004), rather than other Zygomycota, and 2) they are morphologically distinct from other Zygomycota in the way their sporangia are formed and in the frequent production of secondary sporangiospores (Cole and Samson 1979; Benny et al. 2001). Phylogenetic placement of one of the most problematic species, Basidiobolus ranarum, is uncertain (Jensen et al. 1998), but a recent phylogenetic analysis using RPB1 sequence data suggests that it is nested within the Zygomycota (Tanabe et al. 2004). However, this species appears to be distinct from the Entomophthorales with which it has been classified traditionally. Although B. ranarum possesses many of the features of other entomophthoralean species, such as forcibly discharged spores, morphologically similar zygospores, and symbiotic associations with insects (Krejzova 1978; Blackwell and Malloch 1989), this species does not appear to group with other Entomophthorales in molecular phylogenetic studies using SSU rDNA sequences (Nagahama et al. 1995; James et al. 2000). Basidiobolus spp. possess centriole-like nuclear-associated organelles (McKerracher and Heath 1985; Cavalier-Smith 1998), however, only members of the Chytridiomycota, the only flagellated true Fungi, possess functional centrioles.

Though controversial, congruent evidence from alpha- and beta-tubulin gene phylogenies support a zygomycete origin of the microsporidia, a group of highly reduced obligate intracellular parasites of a wide variety of animals including humans (Keeling et al. 2000; Keeling 2003). Because several microsporidian species have emerged as major pathogens of immuno-compromised patients over the past two decades, this enigmatic group has received considerable attention recently by the scientific community. Placement of the microsporidia, however, remains controversial.

The Terms 'Pin' or 'Sugar' Molds

The common names 'pin' or 'sugar' molds are not formal taxonomic names for this group of fungi but refer to their morphological appearance or to one of the most common substrates upon which some members of the Mucorales (Zygomycota) grow. Many members of the Mucorales produce unbranched sporangiophores with a sporangium for a 'head,' a structure that superficially resembles a pin, hence the common name 'pin' molds. Many species commonly cause economically destructive rots of fruits in storage. These fruits, including strawberries and nectarines, are high in simple sugars such as glucose, thereby explaining the origin of this common name. The vast majority of Zygomycota, however, are never encountered by humans and therefore do not have common names.

Glossary

- arbuscular mycorrhizae (AM):

- a symbiotic association of members of the Glomales (Glomeromycota) with plant roots in which the penetrating hyphae produce finely branched haustorial branches (arbuscules), coils, or vesicles.

- centriole:

- cylindrical cellular organelle involved in flagellum formation. Centrioles are approximately 0.3 µm long and 0.1 µm in diameter and are composed of nine sets of triplet microtubules.

- commensalistic:

- a symbiosis in which neither organism is harmed.

- conidium (pl. conidia):

- an asexual spore produced in the fungal phyla Ascomycota and Basidiomycota.

- ectomycorrhizae:

- a mycorrhizal association in which the fungus produces a specialized sheath of hyphae on the surface of the root from which hyphae extend into the soil and into the outer cortical cells of the root.

- endocommensal:

- an organism living as a commensal inside another organism (e.g. Harpellales).

- gametangium (pl. gametangia):

- the specialized cell-type that becomes a fertile gamete producing cell (Fig. 2A) during the sexual cycle.

- haustorium (pl. haustoria):

- a morphologically differentiated hypha, especially one within a cell of the host, which aids in absorption of food.

- heterotrophic:

- of organisms that utilize organic compounds as the primary source of energy.

- merosporangium (pl. merosporangia)

- an elongated sporangiolum producing uniseriate spores (Fig. 6).

- monophyletic:

- a clade or group of organisms that includes a most recent common ancestor and all the descendants from that ancestor.

- mutualism:

- long term, intimate symbiotic association between organisms in which both partners benefit from each other.

- paraphyletic:

- a group of organisms that includes some, but not all, of the descendants from a most recent common ancestor.

- polyphyly:

- a group of organisms that does not include the most recent common ancestor of all the member organisms.

- saprophytic:

- of organisms that utilize dead organic material as food.

- sporangiolum (pl. sporangiola):

- a small sporangium containing one-to-few spores (Figs. 3A, 5, 6, 7, and 9).

- sporangium (pl. sporangia):

- a sac-like structure (Figs. 3B and 8), the contents of which are converted entirely into spores (sporangiospores).

- synapomorphy:

- a shared, derived character; typically a morphological character that defines a clade.

- zygospore:

- a resting spore produced by the fusion of two compatible gametangia (Fig. 2B).

References

Alexopoulos, C. J., C. W. Mims and M. Blackwell. 1996. Introductory mycology. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

Benny, G. L., R. A. Humber and J. B. Morton. 2001. Zygomycota: Zygomycetes. Pp. 113-146. In: The Mycota VII. Systematics and Evolution. Part A. (McLaughlin, D. J., McLaughlin, E. G. and Lemke, P. A., eds.). Springer-Verlag, New York.

Benny G. L. and K. O'Donnell. 2000. Amoebidium parasiticum is a protozoan, not a Trichomycete. Mycologia 92: 1133-1137.

Berbee, M. L. and J. W. Taylor. 2001. Fungal molecular evolution: gene trees and geologic time. Pp. 229-245. In: The Mycota VII. Systematics and Evolution. Part B. (McLaughlin, D. J., McLaughlin, E. G. and Lemke, P. A., eds.). Springer-Verlag, New York.

Berbee, M. L. and J. W. Taylor. 1993. Dating the evolutionary radiations of the true fungi. Can. J. Bot. 71: 1114-1127.

Bidochka, M. J., S. R. A. Walsh, M. E. Ramos, R. J. St. Leger, J. C. Silver and D. W. Roberts. 1996. Fate of biological control introductions: monitoring an Australian fungal pathogen of grasshoppers in North America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 918-921.

Blackwell, M., and D. Malloch. 1989. Similarity of Amphoromorpha and secondary capilliconidia of Basidiobolus. Mycologia 81: 735-741.

Bruns, T. D., R. Vilgalys, S. M. Barns, D. Gonzalez, D. S. Hibbett, D. J. Lane, L. Simon, S. Stickel, T. M. Szaro, W. G. Weisburg and M. L. Sogin. 1992. Evolutionary relationships within the fungi: analyses of nuclear small subunit RNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1: 231-241.

Cavalier-Smith, T. 1998. A revised six-kingdom system of life. Biol. Rev. 73: 203-266.

Cole, G. T. and R. A. Samson. 1979. Patterns of development in conidial fungi. Pitman, London.

de Hoog, G. S., J. Guarro, J. Gene and M. J. Figueras. 2000. Atlas of clinical fungi, second addition. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Baarn and Delft, The Netherlands.

Eslava, A. P., M. I. Alvarez, and M. Delbrück. 1975. Meiosis in Phycomyces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 72: 4076-4080.

Hajek, A. E. 1999. Pathology and epizootiology of Entomophaga maimaga infections in forest Lepidoptera. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63: 814-835.

Heckman, D. S., D. M. Geiser, B. R. Eidell, R. L. Stauffer, N. L. Kardos and S. B. Hedges. 2001. Molecular evidence for the early colonization of land by fungi and plants. Science 293: 1129-1133.

Hesseltine, C. W. 1991. Zygomycetes in food fermentations. The Mycologist 5: 162-169.

Hibbett, D. S., M. Binder, J. F. Bischoff, M. Blackwell, P. F. Cannon, O. E. Eriksson, S. Huhndorf, T. James, P. M. Kirk, R. Lucking, H. T. Lumbsch, F. Lutzoni, P. B. Matheny, D. J. McLaughlin, M. J. Powell, S. Redhead, C. L. Schoch, J. W. Spatafora, J. A. Stalpers, R. Vilgalys, M. C. Aime, A. Aptroot, R. Bauer, D. Begerow, G. L. Benny, L. A. Castlebury, P. W. Crous, Y.-C. Dai, W. Gams, D. M. Geiser, G. W. Griffith, C. Gueidan, D. L. Hawksworth, G. Hestmark, K. Hosaka, R. A. Humber, K. D. Hyde, J. E. Ironside, U. Koljalg, C. P. Kurtzman, K.-H. Larsson, R. Lichtwardt, J. Longcore, J. Miadlikowska, A. Miller, J.-M. Moncalvo, S. Mozley-Standridge, F. Oberwinkler, E. Parmasto, V. Reeb, J. D. Rogers, C. Roux, L. Ryvarden, J. P. Sampaio, A. Schüßler, J. Sugiyama, R. G. Thorn, L. Tibell, W. A. Untereiner, C. Walker, Z. Wang, A. Weir, M. Weiss, M. M. White, K. Winka, Y.-J. Yao and N. Zhang. 2007. A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi. Mycol. Res. 111: 509-547.

James, T. Y., D. Porter, C. A. Leander, R. Vilgalys and J. E. Longcore. 2000. Molecular phylogenetics of the Chytridiomycota supports the utility of ultrastructural data in chytrid systematics. Can. J. Bot. 78: 336-350.

James, T. Y., F. Kauff, C. Schoch, P. B. Matheny, V. Hofstetter, C. Cox, G. Celio, C. Gueidan, E. Fraker, J. Miadlikowska, H. T. Lumbsch, A. Rauhut, V. Reeb, A. E. Arnold, A. Amtoft, J. E. Stajich, K. Hosaka, G.-H. Sung, D. Johnson, B. ORourke, M. Crockett, M. Binder, J. M. Curtis, J. C. Slot, Z. Wang, A. W. Wilson, A. Schüßler, J. E. Longcore, K. ODonnell, S. Mozley-Standridge, D. Porter, P. M. Letcher, M. J. Powell, J. W. Taylor, M. M. White, G. W. Griffith, D. R. Davies, R. A. Humber, J. B. Morton, J. Sugiyama, A. Y. Rossman, J. D. Rogers, D. H. Pfister, D. Hewitt, K. Hansen, S. Hambleton, R. A. Shoemaker, J. Kohlmeyer, B. Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, R. A. Spotts, M. Serdani, P. W. Crous, K. W. Hughes, K. Matsuura, E. Langer, G. Langer, W. A. Untereiner, R. Lücking, B. Büdel, D. M. Geiser, A. Aptroot, P. Diederich, I. Schmitt, M. Schultz, R. Yahr, D. Hibbett, F Lutzoni, D. McLaughlin, J. Spatafora, and R. Vilgalys. 2006a. Reconstructing the early evolution of the fungi using a six gene phylogeny. Nature 443:818-822.

Jensen, A. B., A. Gargas, J. Eilenberg and S. Rosendahl. 1998. Relationships of the insect-pathogenic order Entomophthorales (Zygomycota, Fungi) based on phylogenetic analyses of nuclear small subunit ribosomal DNA sequences (SSU rDNA). Fungal Genet. Biol. 24: 325-334.

Keeling, P. J. 2003. Congruent evidence from alpha-tubulin and beta-tubulin gene phylogenies for a zygomycete origin of microsporidia. Fungal Genet. Biol. 38: 298-309.

Keeling, P. J., M. A. Luker and J. D. Palmer. 2000. Evidence from beta-tubulin phylogeny that microsporidia evolved from within the Fungi. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17: 23-31.

Kirk, P. M., P. F. Cannon, J. C. David, and J. Stalpers. 2001. Ainsworth and Bisby's Dictionary of the Fungi. 9th ed. CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

Krejzova, R. 1978. Taxonomy, morphology and surface structure of Basidiobolus sp. isolate. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 31: 157-163.

Lichtwardt, R. W. 1986. The trichomycetes, fungal associates of arthropods. Springer-Verlag, New York.

Liu, Y., M. C. Hodson, and B. D. Hall. 2006. Loss of the flagellum happened only once in the fungal lineage: phylogenetic structure of kingdom Fungi inferred from RNA polymerase II subunit genes. BMC Evolutionary Biology 6:74.

Lutzoni, F., F. Kauff, C. J. Cox, D. McLaughlin, G. Celio, B. Dentinger, M. Padamsee, D. Hibbett, T. James, E. Baloch, M. Grube, V. Reeb, V. Hofstetter, C. Schoch, A. E. Arnold, J. Miadlikowska, J. Spatafora, D. Johnson, S. Hambleton, M. Crockett, R. Shoemaker, G.-H. Sung, R. Lücking, T. Lumbsch, K. O'Donnell, M. Binder, P. Diederich, D. Ertz, C. Gueidan, K. Hansen, R. C. Harris, K. Hosaka, Y.-W. Lim, B. Matheny, H. Nishida, D. Pfister, J. Rogers, A. Rossman, I. Schmitt, H. Sipman, J. Stone, J. Sugiyama, R. Yahr and R. Vilgalys. 2004. Assembling the fungal tree of life: Progress, classification, and evolution of subcellular traits Am. J. Bot. 91: 1446-1480.

McKerracher, L. J. and I. B. Heath. 1985. The structure and cycle of the nucleus-associated organelle in two species of Basidiobolus. Mycologia 77: 412-417.

Nagahama, T., H. Sato, M. Shimazo and J. Sugiyama. 1995. Phylogenetic divergence of the entomophthoralean fungi: evidence from nuclear 18S ribosomal RNA gene sequences. Mycologia 87: 203-209.

O'Donnell, K. 1979. Zygomycetes in culture. Department of Botany, University of Georgia, Athens.

O'Donnell, K., E. Cigelnik and G. L. Benny. 1998. Phylogenetic relationships among the Harpellales and Kickxellales. Mycologia 90: 624-639.

O'Donnell, K., F. M. Lutzoni, T. J. Ward and G. L. Benny. 2001. Evolutionary relationships among mucoralean fungi (Zygomycota): Evidence for family polyphyly on a large scale. Mycologia 93: 286-296.

Schüßler, A., D. Schwarzott and C. Walker. 2001. A new fungal phylum, the Glomeromycota: phylogeny and evolution. Mycol. Res. 105: 1413-1421.

Tanabe Y., K. O'Donnell, M. Saikawa and J. Sugiyama. 2000. Molecular phylogeny of parasitic Zygomycota (Dimargaritales, Zoopagales) based on nuclear small subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 16: 253-262.

Tanabe, Y., M. Saikawa, M. M. Watanabe and J. Sugiyama. 2004. Molecular phylogeny of Zygomycota based on EF-1 and RPB1 sequences: limitations and utility of alternative markers to rDNA. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 30: 438-449.

Ustinova, I., L. Krienitz and V. A. R. Huss. 2000. Hyaloraphidium curvatum is not a green alga, but a lower fungus; Amobedium parasiticum is not a fungus, but a member of the DRIPs. Protist 151: 253-262.

White, M. M., T. Y. James, K. ODonnell, M. J. Cafaro, Y. Tanabe, and J. Sugiyama. 2006. Phylogeny of the Zygomycota based on nuclear ribosomal sequence data. Mycologia 98: 872-884.

Information on the Internet

- Taxonomy and co-evolution of Trichomycetes (gut-inhabiting fungi) and their Chironomidae (Diptera) hosts.

- Tom Volk's Fungi.

- Fungal Mitochondrial Genome Project.

- The Fifth Kingdom online.

- George Barron's Website on Fungi.

- Deep Hypha Research Corrdination Network. Deep Hypha is a NSF-funded project to coordinate and provide resources for research in fungal systematics.

- AFTOL: Assembling the Fungal Tree of Life. An NSF-funded project to facilitate collaborative research in the phylogeny of Fungi.

- Index Fungorum. World database on fungal names.

Title Illustrations

| Scientific Name | Pilobolus kleinii |

|---|---|

| Comments | Phototropic sporangiophores, each bearing a single black sporangium of the "hat-thrower", Pilobolus kleinii (Mucorales). |

| Acknowledgements | Photo courtesy Malcolm Storey |

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Copyright | © Malcolm Storey |

| Scientific Name | Entomophthora, Delia |

|---|---|

| Comments | Root maggot fly (Delia) killed by the 'insect-destroyer' Entomophthora (Entomophthorales). The fungus has burst through the segments and the abdominal wall. |

| Acknowledgements | Photo courtesy George Barron's Website on Fungi |

| Specimen Condition | Dead Specimen |

| Copyright |

© George Barron

|

About This Page

Two NSF-funded projects, 'Assembling the Fungal Tree of Life' and the 'Deep Hypha' Research Coordination Network (NSF awards DEB-0228657 and DEB-0090301), facilitated the development of this page. Special thanks are due to Robert W. Lichtwardt, George Barron, and Malcolm Storey for permission to reproduce the photos in Figs. 5-9 and the title illustrations.

Timothy Y. James

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

Kerry O'Donnell

National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, Peoria, Illinois, USA

Correspondence regarding this page should be directed to Timothy Y. James at and Kerry O'Donnell at

Page copyright © 2012 Timothy Y. James and Kerry O'Donnell

Page: Tree of Life

Mucoromycotina.

Authored by

Timothy Y. James and Kerry O'Donnell.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

Page: Tree of Life

Mucoromycotina.

Authored by

Timothy Y. James and Kerry O'Donnell.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

- First online 21 December 2004

- Content changed 13 July 2007

Citing this page:

James, Timothy Y. and Kerry O'Donnell. 2007. Mucoromycotina. Version 13 July 2007 (under construction). http://tolweb.org/Zygomycota/20518/2007.07.13 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site