Hyperoartia

Lampreys

Philippe Janvier

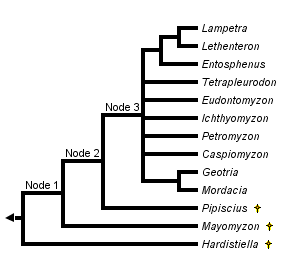

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxThe main characteristics supporting the nodes of this phylogeny are:

Node 1: Piston cartilage in lingual apparatus, loss of anal fin

Node 2: Horny plates or denticles on sucker

Node 3: Seven gill openings, gill pouches larger and more posteriorly placed, eel-shaped aspect.

Introduction

Lampreys are anadromous or fresh water, eel-shaped jawless fishes. They can be readily recognized by the large, rounded sucker which surrounds their mouth and by their single "nostril" on the top of their head. The skin of lampreys is entirely naked ans slimy, and their seven gill openings extend behind the eyes. Whether marine or fresh water, lampreys always spaw and lay eggs in brooks and rivers. During most of their life (about seven years), they are larval; then they undergo a metamorphose and become an adult. Anadromous lampreys, when adult, return to the sea, where they become mature, and live there for one or two years. Then they return to rivers, reproduce and generally die. Many lampreys are parasites. They attach on other fishes by means of their sucker, scrape their skin with their rasping tongue, and suck their blood. All lampreys, however can also feed on small invertebrates. The sucker is also for them a means to travel upstreams in rivers. They use it to attach on stones to rest (Petromyzon, the name of the European lamprey, means "stone sucker") or on more powerful fishes which trail them. Although lampreys are sometimes regarded as a delicacy and fished in Europe, the main cause of their disappearance is water pollution, to which they (in particular larvae) are particularly sensitive.

Recent lampreys, or Petromyzontiformes, include ten genera: Ichthyomyzon, Petromyzon, Caspiomyzon, Geotria, Mordacia, Eudontomyzon, Tetrapleurodon, Entosphenus, Lethenteron, and Lampetra. Lampreys have an amphitropical distribution and are restricted to relatively cold waters. Geotria and Mordacia are the only lampreys of the southern hemisphere, all other genera live in the northern hemisphere.

Characteristics

Lampreys are characterized by:- A large sucker surrounding the mouth, strengthened by an annular cartilage.

- Spine-shaped processes on gill arches

Lampreys are also unique among extant vertebrates in having a median dorsal "nostril", the nasohypophysial opening, but some other fossil vertebrates also display the same structure. It is therefore not diagnostic of lampreys only.

Lampreys are devoid of a mineralized skeleton, although traces of globular calcified cartilage may occur in the endoskeleton.

The head of adult lampreys has relatively large eyes, followed posteriorly by a series of seven, rounded gill openings. Dorsally, there is a translucent pineal spot and, anteriorly to it, a median dorsal "nostril" called the nasohypophysial opening because it is the opening of both the olfactory organ and a blind hypophysial tube including the pituitary gland or hypophysis. This tube is thought to be the remnant of the primitive nasopharyngeal duct (see Hyperotreti). The skin of lampreys is naked and shows large neuromasts of the sensory-line system. The unpaired fins are the dorsal and caudal fins, which are strengthened by numerous, thin cartilaginous radials associated with radial muscles. The tail is slightly hypocercal; that is, the fleshy part containing the notochord is downwardly bent.

The sucker which surrounds the mouth is strengthened by a ring-shaped annular cartilage and bears numerous horny denticles. The depression in the sucker is effected by a complex mechanism which comprises a pumping device, the velum, and a recess of the oral cavity, the hydrosinus. The mouth includes a complex "tongue"-like apparatus which shows some resemblance to that of hagfishes as to its basic mechanism. It bears a series of comb-shaped horny "teeth" which can rotate on the tip of a retractable piston cartilage. The overall resemblance of the "tongue" of lampreys and hagfishes was long regarded as a unique cyclostome character. Considering the current phylogeny, it is now better viewed as independently derived from a basically similar device of the common ancestor to all craniates.

The skull of lampreys is, like that of hagfishes, made up of cartilaginous plates and bars, but it is more complex and includes a true cartilaginous braincase. The gills, although enclosed in muscularized pouches in the adult, are supported by unjointed gill arches (see figure in the Craniata page), which form a "branchial basket". The gill arches lie externally to the gill filaments and associated blood vessels. Lampreys possess, like hagfishes, a very large notochord but, in addition, there are small cartilaginous dorsal arcualia (basidorsals and interdorsals).

The brain has a very poorly developed cerebellum but large optic lobes. The spinal cord is flattened, almost ribon-shaped, yet thicker than that of hagfishes.

The eyes possess a lens, but no intrinsic eye muscles for accomodation. The extrinsic eye muscles are as in extant gnathostomes, except for the superior oblique muscle, which is attached posteriorly in the orbit, instead of anteriorly.

The labyrinth has two vertical semicircular canals, a blind endolymphatic duct, and a number of large ciliated sacs which play a role in equilibrium.

Lampreys undergo a larval development which can last up to seven years. The larval lamprey, or "ammocoetes", has no sucker and poorly developed eyes. Its gills are not enclosed in pouches and it feeds by trapping minute food particles with a strand of mucus produced by the pharynx. Between the mouth and the pharynx, the lamprey larva has a two-valved pumping and anti-reflux device, the velum which, in the adult plays no role in the respiration. The skeleton of the larval head largely consists of a special, elastic tissue, the muco-cartilage, which, during metamorphosis gives rise to a variety of tissues, including true cartilage.

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

The interrelationships of the ten extant genera is still unclear, but it is currently admitted that the organisation of the horny denticles of the sucker in Ichthyomyzon, Petromyzon and Caspiomyzon is primitive for the group. It is also quite similar to that found in one of the fossil lamprey, Pipiscius.

There are three fossil lampreys, Mayomyzon, Hardistiella, and Pipiscius, all from the Late Carboniferous of USA. Mayomyzon is the best known of them and resembles extant lampreys in many respects, except for the somewhat stouter body shape, smaller gill pouches, and coalescent dorsal and caudal fins. Mayomyzon possessed as piston cartilage and, thus, a complex "tongue"-like apparatus. Hardistiella may have retained a small anal fin and a more clearly hypocercal tail. Pipiscius is poorly known but possessed a rouded sucker armed with polygonal horny plates.

Other fossils, formerly referred to the Anaspida are now tentatively regarded as relatives of lampreys. Jamoytius (Early Silurian of Scotland) is a naked jawless craniate which may have possessed an annular cartilage. Euphanerops (Late Devonian of Canada) looks like a naked anaspid, with a strongly hypocercal tail, and also seems to have an annular cartilage. Some, however, still put this genus, as well as Endeiolepis among anaspids.

References

Arsenault, M. and Janvier, P. (1991). The anaspid-like craniates of the Escuminac Formation (Upper Devonian) from Miguasha (Québec, Canada), with remarks on anaspid-petromyzontid relationships.In Early vertebrates and related problems of evolutionary biology (ed. M. M.Chang, Y. H. Liu, and G. R. Zhang) pp. 19-40, Science Press, Beijing.

Bardack, D., and Richardson, E. S. Jr. (1977). New agnathous fishes from the Pennsylvanian of Illinois. Fieldiana: Geology, 33, 489-510.

Bardack, D. and Zangerl, R. (1971). Lampreys in the fossil record. In The Biology of lampreys (ed. M. W. Hardisty and I. C. Potter), Vol. 1, pp. 67-84. Academic Press, London.

Forey, P. L., and Gardiner, B. G. (1981). J. A. Moy-Thomas and his association with the British Museum (Natural History). Bulletin of the British Museum (natural History), Geology, 35, 131-144.

Hardisty, M. W. and Potter, I. C. (ed.) (1974-1982). The Biology of Lampreys, 4 vols, Academic Press, London.

Janvier, P. (1996). Early vertebrates. Oxford Monographs in Geology and Geophysics, 33, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Janvier, P., and Lund, R. (1983). Hardistiella montanensis n. gen. et sp. (Petromyzontida) from the Lower Carboniferous of Montana, with remarks on the affinities of the lampreys. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 2, 407-413.

Marinelli, W. and Strenger, A. (1954). Vergleichende Anatomie und Morphologie der Wirberltiere. Lampetra fluviatilis. Franz Deuticke, Vienna.

Potter, I. C. and Hilliard, R. W. (1987). A proposal for the functional and phylogenetic significance of differences in the dentition of lampreys (Agnatha: Petromyzontiformes). Journal of Zoology, 212, 713-737.

Title Illustrations

| Scientific Name | Hyperoartia, Mayomyzon |

|---|---|

| Location | Illinois |

| Comments | Some modern lampreys (top) are external parasites of other fishes and suck their blood by attaching to their prey by means of a large sucker surrounding their mouth. Lampreys have a single, median and dorsal "nostril", the nasohypophysial opening, which is situated anteriorly to the eyes. One of the earliest known fossil lamprey, Mayomyzon (bottom), from the Late Carboniferous of Illinois, may not have been such a parasitic form and had a stouter body than modern lampreys). |

| Reference | Bardack, D. and Zangerl, R. (1971). Lampreys in the fossil record. In The Biology of lampreys (ed. M. W. Hardisty and I. C. Potter), Vol. 1, pp. 67-84. Academic Press, London. |

| Acknowledgements | after Bardack, D. and Zangerl, R. (1971). Lampreys in the fossil record. In The Biology of lampreys (ed. M. W. Hardisty and I. C. Potter), Vol. 1, pp. 67-84. Academic Press, London. |

| Specimen Condition | Fossil -- Period: Late Carboniferous |

| Image Use |

This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License - Version 3.0. This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License - Version 3.0.

|

| Copyright |

© 1997

|

About This Page

Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle Paris, France

Page copyright © 1997

Page: Tree of Life

Hyperoartia. Lampreys.

Authored by

Philippe Janvier.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

Page: Tree of Life

Hyperoartia. Lampreys.

Authored by

Philippe Janvier.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

Citing this page:

Janvier, Philippe. 1997. Hyperoartia. Lampreys. Version 01 January 1997 (under construction). http://tolweb.org/Hyperoartia/14831/1997.01.01 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site