Struthio camelus massaicus male, Masai Mara Game Reserve, Kenya, © 2002 California Academy of Sciences; Struthio camelus camelus male, Hai-Bar Nature Reserve, Arava Desert, Israel; © 2006 Judith Anenberg, Struthio camelus australis female, Cape of Good Hope, South Africa, © 2008 Clifton Beard.

Introduction

Struthio camelus is the largest living bird species on the Earth, and among the most unique. The species name Struthio camelus comes from the Greek words meaning 'camel sparrow'. This name was chosen by the Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus to describe the elongated neck of the species, an often identifying characteristic. The ostrich is endemic to Africa but can be seen worldwide in zoos and wildlife refuges.

Classification

The classification shown below is generally agreed upon by the scientific community. The ostrich is part of the modern birds (Neornithes), but then diverges into the superorder Palaeognathae, while most living bird species belong to the superorder Neognathae. The unique palate morphology of the Palaeognathae is what separates them into a unique group.

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Subclass: Neornithes

- Superorder: Palaeognathae

- Order: Struthioniformes

- Family: Struthionidae

- Genus: Struthio

- Species: Struthio camelus

The order Struthioniformes consists of birds classified as ratites. Ratites are a group of flightless birds found all over the globe. Common constituents of this group are ostriches, emus, rheas, cassowarys, and kiwis. The ratites form a group based on a proposed vicariance hypothesis. This hypothesis states that the different species of ratites developed as a result of the supercontinent Gondwana breaking apart and separating the ancestral species into exclusive sects.

Evidence for this hypothesis came from a study conducted by Haddrath and Baker (2001) who sequenced the mitochondrial DNA of various ratite species. Their study compared the sequences of the various species within the ratites and concluded that these molecular data support the vicariance hypothesis. Morphological data such as a lack of keel on the sternum of ratite species lends further support to this hypothesis.

Within the ratites there is still debate as to how the different genera are organized. Recent research by Haddrath and Baker (2001) as well as work by Cooper et al. (2001) shows either the Rheidae (Rheas) or Dinornithidae (Moas) as the basal group, and then the Struthionidae coming off of this. There is still no consensus as to where to place the Aepyornithidae (elephant birds) within the ratites.

Another controversy with ostrich classification is the presence or absence of a fifth subspecies. Based off of morphological studies the Somali Ostrich (Struthio molybdophanes) was considered to be a subspecies of Struthio camelus. A mitochondrial DNA study conducted by Freitag and Robinson (1993) showed a definite distinction between the Somali subspecies and the other subspecies present in Northern Africa. Currently, as is seen on The Tree of Life Website, Struthio molybdophanes is considered an independent species.

Subspecies

There are four distinct subspecies of Struthio camelus that each occupy their own niche. Previously there would have been five subspecies, but Struthio molybdophanes is now considered a unique species.

- Struthio camelus australis - Commonly called the Southern Ostrich because it is found exclusively in Southern Africa. Lives in a range independent of all other supspecies of ostrich.

- Struthio camelus camelus - The largest and most widespread of the ostrich subspecies. Commonly called the North African Ostrich or the Red-necked Ostrich.

- Struthio camelus massaicus - This subspecies, referred to as the Masai Ostrich, lives in Eastern Africa and is easily identified by the bright orange neck and thighs of the males.

- Struthio camelus syriacus - Endemic to the Arabian Peninsula, Syria, and Iraq, the Arabian or Middle Eastern Ostrich used to be very common. Due to overhunting and habitat restrictions, this subspecies became extinct around 1966.

Evolution

The oldest fossil which currently represents the earliest ostrich-like species was found in Central Europe and dates back to the middle Eocene. The species Palaeotis was a moderately sized bird with the characteristic lack of flying ability found in ratites. Originally, Palaeotis was not considered to be part of the ostrich family, but further research showed that it was an ancestral form.

After the documentation of Palaeotis, the ostrich fossil record takes a break until the Early Miocene, a gap of approximately 15 million years. Many fossils have been found in Africa, Asia, and Europe which date back to this time period. These fossils were characteristic of species from the genus Struthio, which still has living representatives today.

African Struthio evolution is very well documented and follows a fairly delineated pathway. However, the evolution of Struthio species in Asia is less clear. A reason for this is the lack of complete fossils from which paleobiologists may piece together evolutionary histories. At the moment, Asian ostrich evolution and its link to African ostrich evolution is sketchy at best, but further fossil evidence should help to elucidate a better understanding.

Distribution and Habitat

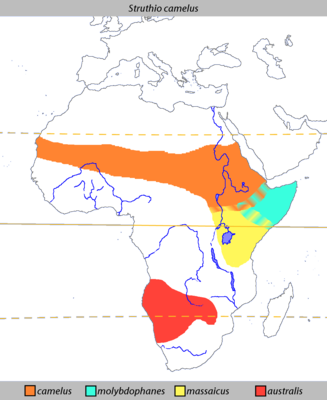

Wild ostriches are found exclusively in Africa. The diagram below shows the distribution of the three living Struthio camelus subspecies, as well as Struthio molybdophanes. As noted above subspecies syriacus is extinct and thus has no current distribution.

Struthio camelus distribution. Struthio camelus camelus (orange) occupies a large area that stretches across the continent. This area overlaps with the Sahel region of Africa; a semi-arid savanna region south of the Sahara. The massaicus subspecies (yellow) occupies a region to the south-east of the Sahel, near Kenya. The australis subspecies (red) has an independent distribution in southern Africa, south of the Zambezi and Cunene rivers.

All three of the subspecies occupy savanna regions with semi-arid, tropical conditions. These regions are found both north and south of the forests that are found in the equitorial regions of Africa.

Struthio camelus running through its savanna habitat in Serengeti National Park, © 2004 Eyal Bartov.

Physical Characteristics

Size

- Males range in height from 6 to 9 ft (1.8 to 2.7 m) and females range from 5.5 to 6.5 ft (1.7 to 2 m)

- Weigh between 200 and 350 lbs (90 to 160 kg)

- Wingspan of around 2 meters

Colouration

- Males have black plumage with white at the ends. Female feathers are generally shades of brown and blend in better with the surroundings.

- Males' thighs and necks are pink in the camelus subspecies and orange in the massaicus subspecies. Females have a whiter/browner complexion. Most ostriches look like they have a brown neck and legs because of dust bathing.

Locomotion

- Lack of flying ability.

- Powerful legs for running with strides between 10 and 16 feet (3 to 5 meters).

- Can maintain speeds of 50 kilometers an hour.

- Speed bursts exceeding 65 kilometers an hour.

- Fastest two legged-animal.

Senses

- Excellent vision.

- Largest eye of any land animal.

- Acute hearing as well for predator detection.

Other Features

- Elongated neck characteristic of the species.

- Only 2 toes, as opposed to 4 for most birds. Also have a large claw on foot.

- Ostriches have an average lifespan of 30 to 40 years and can reach 70 years old.

Behaviour

Ostriches have many unique behavioural characteristics that suit their morphology. Ostriches are primarily herbivores, feeding on nuts, flowers, seeds, and leaves. Occasionally, ostriches will eat insects such as locusts. Ostriches have beaks and no teeth; they eat pebbles with their food which aids in grinding it down. Ostriches have gained the ability to survive a long time without water, but will drink and bathe whenever possible. While eating or drinking, ostriches will frequently raise their long necks in the air to look for potential predators.

Ostriches typically travel in nomadic groups of 5 to 12 individuals. An alpha male is in control of these herds and will mate with the dominant female. Territories can range from 2 to 15 square kilometers depending on the area. Ostriches will sometimes lie completely flat on the ground, with the neck stretched to the extreme. This behaviour helps to camouflage the ostrich in the savanna grasses, and is particularly effective for females with brown colouration. If ostriches detect predators they will usually run away, but if cornered or too slow they can deliver powerful kicks with their legs that can severely injure or kill an animal

A unique behaviour shown by ostriches is their method of temperature regulation. In the savanna, temperatures vary greatly between day and night. The ostrich uses its wings to either cover or uncover its upper legs. In the winter, the ostrich will cover its body with its wings to trap heat in and maintain a high body temperature. During the summer, the ostrich will relax its wings from its body in order to allow heat to dissipate.

Ostrich communication is rather limited because they are fairly independent animals. Ostriches primarily whistle, growl, or boom. In general, most common ostriches are rather silent. Communication increases during mating season when males are competing and trying to impress females.

Reproduction

The reproductive life cycle of ostriches begins once they reach sexual maturity. This can range from 2 to 4 years, with females maturing slightly quicker. Mating season begins at the start of the dry season.

Courtship

Males will fight for the right to mate with a harem of females (typically 5 to 7). Fights will involve loud hissing and large feather displays to scare away other males. Once a male has achieved dominance, he will find the dominant female and engage in a sort of dance.

Mating

After this brief courtship the dominant male will copulate with all the females in the harem, but will only pair with the dominant one. The female ostriches will crouch on the ground and be mounted by the male.

Nesting and Eggs

The dominant male will dig out a depression in the ground to be used as a nest for the eggs. Although there are many females, only the dominant female's nest is used for all of the eggs. The dominant female's eggs will get preferential positioning in the nest. Each female in the harem will lay between 2 and 12 eggs. Ostrich eggs are the largest eggs in the world, weighing on average 1.5 kg. These eggs are cream coloured with thick shells. Only 10% of these eggs will actually hatch.

The nest is guarded and incubated during the day by the female, whose brown colouration serves as excellent camouflage. At night, the male will take over with incubation, because their black feathers make them almost undetectable.

Birth and Youth

The gestation period of ostriches is between 35 and 45 days. Once hatched, the male will defend the chicks. While defending, the male will teach the chicks how and on what to feed. By the end of their first year, the chicks will have already reached their full height. Young ostritches are at high risk of predation, but once matured their survival rate is high.

Ostriches and Humans

There has been a long and well documented history of interaction between ostriches and humanity. Throughout history, humans have used these unique animals for food, clothing, sports, and even cleaning. This section will look at some of the past and current uses of ostriches in society.

Food

Ostrich meat is considered by some to be a delicacy, in addition to being a healthy source of protein, iron, and calcium. Currently, there are many ostrich farms around the world that raise these birds much like cattle. In addition to slaughtering them for meat, ostrich eggs are another valued commodity.

Clothing

The use of ostriches in fashion nearly drove the species to extinction during the 18th century. Ostrich feathers were once considerd a fashion item and sparked the creation of ostrich farms in the 19th century. The use of ostrich feathers in fashion has died out, but ostrich leather is still a valued commodity. Ostrich leather is considered extremely strong and has also been used in the manufacturing of clothing.

Sports

The use of ostriches in entertainment began in Roman times (around 50 AD) where they were sometimes chosen to fight men in amphitheaters. This practice led to the deaths of thousands of animals. Currently, because of their size, ostriches are sometimes raced by small humans in competition. This practice has generated immense opposition from animal rights activists.

Cleaning

Perhaps the most well known use of ostriches is in the feather duster. Since 1900, dusters made from ostrich feathers have been manufactured and used all over the world. The appealing part about ostrich feathers is that they produce a static charge which clings to dust, are easily washable, and are durable. The advantage of farming ostriches for feathers is that the birds are unharmed in the process.

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site