Heliconius

Margarita Beltrán, Andrew V. Z. Brower, and Chris Jiggins

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxIntroduction

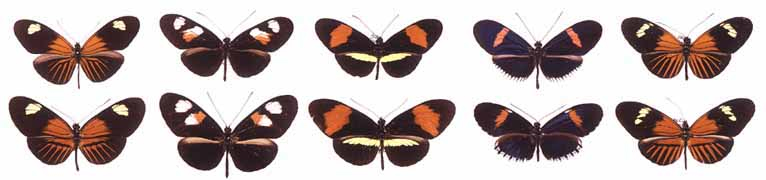

The Heliconius butterflies are the most speciose genus within the Heliconiini, displaying a dramatic diversity of colour patterns at species and sub-species level. They are also famous for Müllerian mimicry, with many species converging on a common wing pattern where they live together. Heliconius communities commonly consist of several ‘mimicry rings’, groups of species that share a common pattern.

Colour pattern diversity of H. numata (top two rows), and H. melpomene (third row) with its co-mimic H.erato (bottom row).

Heliconius butterflies have two unique, derived ecological traits that may have facilitated rapid adaptive radiation: pollen feeding and pupal-mating behaviour (Gilbert, 1972). Adult butterflies systematically collect pollen from flowers, which they masticate on the proboscis to dissolve out amino acids. This allows caterpillars to develop relatively rapidly (since they do not need to store nutrients for egg and sperm production), and allows adults to have a greatly extended lifespan – up to 8 months – in the wild.

Heliconius butterflies with proboscis bearing pollen collected from flowers. The diets of most Lepidoptera are very limited in nitrogenous compounds, and pollen feeding is thought to increase longevity and egg production in Heliconius butterflies. Images ©

The pollen-feeding behaviour centres around a group of vines in the Cucurbitaceae, Psiguria and Gurania. This is a tight plant-pollinator relationship in which the butterflies are major pollinators for the plants and the plants major food resources for adult maintenance and egg production. 80% of a female's egg production come from amino acids that come from pollen she collects. Only 20% comes from amino acids acquired by the caterpillars feeding on passion vines. In most butterflies and moths, 100% of eggs derive from the efforts of the larval stage, and eggs are laid in a quick pulse after adult emergence. In Heliconius, eggs are laid as they are manufactured over the adult's long lifespan (Gilbert, 1972). The butterflies learn the locations of pollen plants and establish home ranges based on pollen foraging routes. It appears that the pollen plants are more significant than larval hosts in determining a female's assessment of the habitat. Thus, as long as she knows the locations of a network of pollen plants, she will stay in the area, even during periods when new shoots of passion vine hosts are temporarily not available due to weather or defoliation by Heliconius or other competing herbivores. So while most herbivorous insects disperse away when suitable oviposition sites are scarce, Heliconius females are content to stay put as long as the mutualist plant produces pollen (which is year-round). Moreover the pollen promotes a long reproductive life so that females can wait many weeks for the opportunity to resume egg-laying (Ehrlich & Gilbert, 1973).

Heliconius sapho male sitting on a female pupa. Mating takes place as the female begins to eclose, and females mate only once. ©

A second unusual trait found in some Heliconius species is a unique mating behaviour known as pupal-mating. Males of certain species search larval food plants for female pupae. The males then sit on the pupae a day before emergence, and mating occurs the next morning, before the female has completely eclosed (Gilbert, 1976; Deinert et al. 1994). Various kinds of pupal-mating occur scattered across several insect orders (Thornhill & Alcock, 1993); in passion-vine butterflies almost half the Heliconius species (42%) are pupal-maters (Gilbert, 1991, pupal mating clade marked in the cladogram above).

Gilbert (1991) suggested that pupal-mating might play an important role in the radiation of Heliconius as well as in the packing of Heliconius species into local habitats. Pupal-mating might enhance the possibility of intrageneric mimicry because in many cases, mimetic species pairs consist of a pupal-mating and a non pupal-mating species. The strikingly different mating tactics of these groups could allow phenotypically identical species to occupy the same habitats without mate recognition errors. Second, this mating tactic may influence host-plant specialisation, as it has been suggested that pupal-mating species may displace other heliconiines from their hosts by interference competition (Gilbert, 1991). Males of these species sit on, attempt to mate with, and disrupt eclosion of other Heliconius species of both mating types encountered on the host plant. This aggressive behaviour may prevent other heliconiine species from evolving preference for host plants used by pupal-mating species.

Etymology: Heliconius signifies dwellers on Mount Helicon (Turner, 1976) (see each species for more information). Helicon is a mountain in southern Greece, in Boeotia, regarded in ancient Greece, as the source of poetry and inspiration. From it flowed the fountains of Aganippe and Hippocrene, associated with Muses. The nine Muses are daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory. The Muses sat near the throne of Zeus, king of the gods, and sang of his greatness and of the origin of the world and its inhabitants and the glorious deeds of the great heroes. From their name words such as music, museum, mosaic are derived (Muses). The nine muses are:

- Calliope Epic and heroic poetry and the head muse

- Clio History

- Erato Love-poetry

- Euterpe Music and Lyric poetry

- Melpomene Tragedy

- Polyhymnia Sublime hymns or serious sacred songs

- Terpsichore Dancing and choral song

- Thalia Comedy and idyllic poetry

- Urania Astronomy

- Stalachtis calliope (L.), 1758 (Riodinidae)

- Eresia clio (L.), 1758 (Nymphalinae)

- Heliconius erato (L.), 1758

- Stalachtis euterpe (L.), 1758 (Riodinidae)

- Heliconius melpomene (L.), 1758

- Mechanitis polymnia (L.), 1758 (Ithomiini) (a variant spelling of Polyhymnia)

- Acraea terpsichore (L.), 1758 (Acraeini, African)

- Actinote thalia (L.), 1758 (Acraeini)

- Taenaris urania (L.), 1758 (Amathusiini, Australasian)

Characteristics

Heliconius are recognized by their large eyes, long antennae, characteristic elongate wing-shape, teardrop-shaped hindwing discal cell, and distinctive colour patterns. The hostplants are all Passifloreae, and there is some phylogenetic association between species groups of Passiflora and the Heliconius species that feed on them (Benson et al., 1976; Brower, 1997) (see each species for more details).

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

For discussion of the monophyly of the genus as presented here and relationships among heliconiine genera, see the Heliconiini page. Within Heliconius the relationships presented here are based on molecular sequence data for 3 mtDNA and 4 nuclear gene regions (Beltran et al. 2007). There is also a highly supported monophyletic ‘pupal-mating clade’ suggesting that pupal mating behaviour evolved only once in the Heliconiina (see tree above). Within Heliconius, the absence of a signum on the female bursa copulatrix is a morphological character that defines the pupal-mating group (Penz, 1999).

Geographic Distribution

Membeers of the genus are found from the southern United States throughout Central and South America and the West Indies, with the greatest diversity of species in the Amazon Basin (Emsley, 1965; DeVries, 1987).Heliconius butterflies show a continuum of geographic divergence and speciation; they are unpalatable and exhibit inter- and intraspecific diversification of colour and patterns. Bates’ classic paper (Bates, 1862), reflecting observations during his stay in the Amazon, showed a geographical pattern for the different colour forms: similar between species within any one area of the Amazon basin, but the mimetic colour patterns themselves changed every 100-200 miles. Beside this geographic divergence, closely related species within an area often belonged to mimicry “rings” (groups of unpalatable species, together with some palatable species, that have converged on the same warning colour pattern) (Brower et al., 1964; Mallet and Gilbert, 1995). Bates’ system has all the intermediate stages between local varieties, geographic races, and sympatric species that make it an excellent biological model to study selection, hybridization and gene flow at the species boundary. See maps attached to each species.

Co-mimetic species such as H. erato (top) and H. melpomene (bottom) have frequently evolved a diversity of geographic races or sub-species. The two species look identical in any one locality but their patterns change in concert across their geographic range; Localities left to right: Zamora, Ecuador; Puyo, Ecuador; Tarapoto, Peru; Guayaquil, Ecuador; Yurimaguas, Peru. © 1999 James Mallet

Other Names for Heliconius

- Heliconius

- Migonitis

- Sunias

- Ajantis

- Apostraphia

- Sicyonia

- Heliconia

- Laparus

- Crenis

- Phlogris

- Podalirius

- Blanchardia

References

Bates, H. W. 1862. Contributions to an insect fauna of the Amazon Valley. Lepidoptera: Heliconidae. Trans. Linn. Soc. Lond. 23:495-566.

Beltr?n M, Jiggins CD, Brower AVZ, Bermingham E, Mallet M. 2007. Do pollen feeding, pupal-mating and larval gregariousness have a single origin in Heliconius butterflies? Inferences from multilocus DNA sequence data. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society in press.

Beltr?n M, Jiggins CD, Bull V, Linares M, Mallet J, McMillan WO, and Bermingham E. 2002. Phylogenetic discordance at the species boundary: comparative gene genealogies among rapidly radiating Heliconius butterflies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19: 2176-2190.

Benson WW, Brown KS, Gilbert LE 1976. Coevolution of plants and herbivores: passion flower butterflies. Evolution 29, 659-680.

Brower, A. V. Z. 1997 The evolution of ecologically important characters in Heliconius butterflies (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae): a cladistic review. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 119, 457-472.

Brower AVZ, and Egan MG. 1997. Cladistics of Heliconius butterflies and relatives (Nymphalidae: Heliconiiti): the phylogenetic position of Eueides based on sequences from mtDNA and a nuclear gene. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 264: 969-977.

Brower, L. P., Brower, J. v. Z. & Collins, C. T. 1963 Experimental studies of mimicry 7: relative palatability and Mullerian mimicry among neotropical butterflies of the subfamily Heliconiinae. Zoologica 48, 65-84.

Brown KS, Jr. 1981. The biology of Heliconius and related genera. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 26: 427-456.

Deinert EI. Longino JT, Gilbert LE. 1994. Mate competition in butterflies. Nature 370: 23-24.

DeVries P. J. 1987 The Butterflies of Costa Rica and Their Natural History, Volume I: Papilionidae, Pieridae, Nymphalidae Princeton University Press, Baskerville, USA.

Ehrlich PR, Gilbert LE. 1973 Population structure and dynamics of the tropical butterfly Heliconius ethilla. Biotropica 5: 69-82.

Emsley MG. 1965. Speciation in Heliconius (Lep., Nymphalidae): morphology and geographic distribution. Zoologica NY 50: 191-254.

Gilbert LE. 1972. Pollen Feeding and Reproductive Biology of Heliconius Butterflies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 69: 1403-1407.

Joron M, Papa R, Beltr?n M, Chamberlain N, Mav?rez J, Baxter, S, Abanto, M, Bermingham, E, Humphray, SJ, Rogers, J, Beasley, H, Barlow, K, ffrench-Constant, RH, Mallet, J, McMillan, WO, Jiggins, CD. 2006. A conserved supergene locus controls colour pattern diversity in Heliconius butterflies. PLoS Biology Vol. 4, No. 10, e303 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040303

Linnaeus, C. 1758 Systema Naturae, (10th edn., facsimile reprint, 1956). London: British Museum (Natural History).

Mallet J. Singer MC. 1987. Handling effects in Heliconius: where do all the butterflies go? J. Animal Ecology. 56: 377-386.

"Muses." Encyclopedia Mythica from Encyclopedia Mythica Online. http://www.pantheon.org/articles/m/muses.html [Accessed May 22, 2008].

Penz CM. 1999. Higher level phylogeny for the passion-vine butterflies (Nymphalidae, Heliconiinae) based on early stage and adult morphology. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 127: 277-344.

Turner, J.R. 1976. Adaptive radiation and convergence in subdivisions of the butterfly genus Heliconius (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 58(4): 297-308.

Information on the Internet

- www.heliconius.org. Everything about Heliconius.

- Chris Jiggins homepage. Genetic linkage mapping of the Heliconius genome to search for regions controlling traits of interest

- Los Heliconiini (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae) de Venezuela . An excellent resource for Venezuelan species.

- Heliconius phylogeny homepage. Photos and data from our Heliconiine phylogeny study.

- James Mallet homepage. Information on mimicry and Heliconius in general.

- Mathieu Joron homepage.Information about Heliconius numata

- Owen McMillan Lab. Mapping colour pattern genes in Heliconius erato.

- Robert D. Reed. Evo-devo of Heliconius wing patterns

- Insect Flight Research. Butterfly flight , including mimicry in flight patterns.

- L.E. Gilbert homepage. Ecology and behaviour.

- Briscoe Lab. Molecular evolution of eye pigment genes .

Title Illustrations

| Scientific Name | Heliconius hierax |

|---|---|

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Image Use |

This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License - Version 3.0. This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License - Version 3.0.

|

| Copyright |

© Chris Jiggins

|

| Scientific Name | Heliconius atthis |

|---|---|

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Image Use |

This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License - Version 3.0. This media file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License - Version 3.0.

|

| Copyright |

© Chris Jiggins

|

About This Page

University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, Tennessee, USA

Chris Jiggins

University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

Correspondence regarding this page should be directed to Margarita Beltr?n at , Andrew V. Z. Brower at , and Chris Jiggins at

Page copyright © 2010 , , and Chris Jiggins

Page: Tree of Life

Heliconius .

Authored by

Margarita Beltr?n, Andrew V. Z. Brower, and Chris Jiggins.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

Page: Tree of Life

Heliconius .

Authored by

Margarita Beltr?n, Andrew V. Z. Brower, and Chris Jiggins.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

- First online 18 February 2007

- Content changed 08 March 2010

Citing this page:

Beltrán, Margarita, Andrew V. Z. Brower, and Chris Jiggins. 2010. Heliconius . Version 08 March 2010. http://tolweb.org/Heliconius/72231/2010.03.08 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site