Odontoceti

Toothed whales

Michel C. Milinkovitch and Olivier Lambert

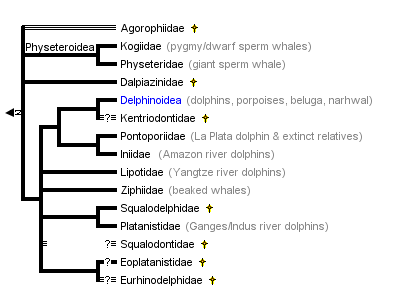

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxCharacteristics

Extant odontocetes catch individual prey: fish, cephalopods (e.g., ziphiids and physeterids mainly eat squids in abyssal waters), and small crustaceans, but also marine mammals (e.g., some killer whale populations mainly feed on pinnipeds). Their feeding behavior is greatly helped by their echolocation abilities (cf. below).

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

Physeteroidea (Physeteridae and Kogiidae)

The highly-derived morphology of their skull (related to the development of the spermaceti organ) leads to important difficulties in the establishment of the polarity of some characters. Some molecular studies based on mitochondrial DNA sequences (Milinkovitch et al. 1993; Milinkovitch et al. 1994) suggest that Physeteroidea are more closely related to mysticetes than they are to other odontocetes. However, other molecular data (e.g., Nikaido et al. 1999; Gatesy et al. 1999) support the monophyly of toothed whales (Odontoceti). Recent analyses (Cassens et al. 2000) indicate that there is conflicting signal between the nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA data. Whether this conflict is due to differential lineage sorting or to misleading signal from one or several data set(s) remains to be investigated.

Furthermore, the monophyly of toothed whales is supported by derived morphological character states such as: maxillae covering the supraorbital region, single blowhole, development of a melon, development of proximal sacs (Heyning, 1989), most of the lateral side of the periotic detached from the squamosal except for a small area near the hiatus epitympanicus (Luo and Gingerich, 1999). A sister-group relationship between sperm and baleen whale would prompt reappraisal of morphological transformations in cetaceans (Milinkovitch, 1995).

Note that some morphological analyses have placed the Physeteroidea as the sister-group to the Ziphiidae in a clade Physeterida characterized by (among others):

- The development of a large posterior process of the tympanic (Muizon, 1990);

- An extreme reduction of the tuberculum of the malleus (Muizon, 1990);

- An enlarged, subspherical, and fused (to periotic) accessory ossicle of the periotic (Fordyce, 1994).

The special case of the so-called "river dolphins"

While most of the 83 recognized extant species of cetaceans are exclusively marine, several species live sporadically or exclusively in fresh water. Some of them (e.g., beluga, Tucuxi, Irrawaddy dolphin, finless porpoise) are well characterized phylogenetically, i.e., they belong to the superfamily Delphinoidea (see, e.g., Heyning, 1989; LeDuc et al., 1999). On the other hand, the taxonomic relationships of the so-called "river dolphins" have been in a state of confusion for more than a century. These include three exclusively riverine species:

- The blind river-dolphin, or "susu" (Platanista gangetica) living in the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra river systems on the Indian sub-continent;

- The Yangtze river-dolphin, or "baiji" (Lipotes vexillifer) which lives in the lower and middle reaches of the Yangtze river in China, and

- The Amazon river-dolphin, or "boto" (Inia geoffrensis) which is largely distributed in northern South America in the Orinoco and Amazon River systems, and the upper Rio Madeira drainage.

The fourth species classified as a "river dolphin" is the La Plata dolphin, or "franciscana" (Pontoporia blainvillei). It is found not only in estuaries but also in coastal waters of eastern South America from 19°S (Brazil) to 42°S (Argentina).

All "river dolphins" show a peculiar morphology with a characteristic long and narrow rostrum, a low triangular dorsal fin, broad and visibly fingered flippers, and a flexible neck. Their eyes have also been reduced to various degrees (Pilleri 1974; the susu even lacks eye lenses and is virtually blind) while echolocation abilities seem more refined than in other cetaceans. In addition, shared skull characters led most authors to classify them into a monophyletic group, either in the family Platanistidae or in the superfamily Platanistoidea (sensu lato, Flower 1869; Cozzuol 1985). However, these diagnosing characters could be ancestral (Rice 1998; Messenger 1994), hence phylogenetically uninformative, or prone to convergence (because adaptive to living in turbid waters). While the monophyly of the group was usually not questioned, many morphological analyses emphasized the substantial divergence among the four species (e.g., Kasuya 1973; Zhou et al. 1979), and this eventually led to the classification of the four genera in four monotypic families (Pilleri 1980; Zhou 1982).

Morphological idiosyncrasies as well as the separation of the four species on three subcontinents have created taxonomic disagreement among morphologists with continuing debate regarding the reality of a river dolphin clade and the position(s) of “river dolphins” within the phylogeny of whales. Gray (1863) first challenged the monophyly of "river dolphins" and was followed by other authors who included the fransiscana within delphinids (Kellogg 1928; Miller 1923). Only recently, morphologists revisited Gray's hypothesis. Heyning (1989) recognized a clade including the boto, fransiscana, and baiji . On the other hand, de Muizon (1985;1994), as well as Messenger and McGuire (1998), defined the Delphinida clade, grouping the baiji with the monophyletic [boto , fransiscana , Delphinoidea]. Morphological characters supporting the Delphinida are:

- Acquisition of a lateral lamina on palatine, virtual loss of posterior region of lateral lamina of pterygoid, excavation of postero-dorsal region of involucrum of tympanic (Muizon, 1988);

- Evolution of a vestibular sac (Heyning, 1989);

- Loss of anterior bullar facet on periotic (Fordyce, 1994);

Phylogenetic analyses of nucleotide sequences (from mitochondrial and nuclear genes) confirmed that extant river dolphins are not monophyletic (Cassens et al. 2000; Hamilton et al. 2001) and suggest that they are relict species whose adaptation to riverine habitats incidentally ensured their survival against major environmental changes in the marine ecosystem or the emergence of Delphinidae (Cassens et al. 2000). This work (Cassens et al. 2000) based on nucleotide sequence analyses (cytochrome b, partial 12S rDNA and partial 16S rDNA) and others (Nikaido et al. 2001) based on the analysis of SINE retropositions also support the monophyly of Delphinida.

The restricted family Platanistidae (including the extant Platanista and several Miocene marine relatives) is placed in recent molecular studies as the sister-group of Delphinida , Ziphiidae (Cassens et al. 2000; Hamilton et al. 2001), a result which is not consistent with the main recent morphological studies, that maintain the superfamily Platanistoidea (including Platanistidae and two fossil families Squalodontidae and Squalodelphinidae) as sister-group of the Delphinida , Eurhinodelphinoidea (Muizon 1991) or as sister-group of all the extant odontocete families, including the Physeteroidea (Fordyce 1994).

Discussion of some problematic extinct groups

Several fossil groups of odontocetes (e.g., Agorophiidae, Squalodontidae, Eurhinodelphinidae, and Kentriodontidae) are still taxonomically problematic; it is very likely that some of them form paraphyletic groups.

- The poorly known Late Oligocene Agorophiidae probably form a grade in which all the primitive heterodont odontocetes retaining intertemporal dorsal exposition of the parietals (a primitive character which places them as a morphological link between archaeocetes and Squalodontidae; Rothausen, 1968) have been grouped (e.g., Agorophius, Archaeodelphis and Xenorophus; reviewed in Fordyce, 1981). A new family Simocetidae was recently proposed for the agorophid-like dolphin Simocetus, from the Oligocene of the Eastern North Pacific, indicating a more important morphological diversity among these archaic odontocetes (Fordyce, 2002).

- The family Squalodontidae has long been recognized as very basal among odontocetes. This Late Oligocene to Late Miocene taxon is characterized by primitive heterodont teeth. However, some derived characters of the scapula suggest phylogenetic affinities with Platanistidae and Early Miocene Squalodelphinidae (Muizon, 1987; Fordyce, 1994). The family Dalpiazinidae, including the small and nearly homodont early Miocene Dalpiazina ombonii, has been loosely attached to squalodontids (Muizon, 1991). The monogeneric heterodont family Waipatiidae, known for now from the Late Oligocene of New Zealand is either related to the clade (Platanistidae , Squalodelphinidae) (Fordyce, 1994), to the clade (Eurhinodelphinidae , Ziphiidae) (Lambert, 2005), or basal to crown-Cetacea (Geisler & Sanders, 2003).

- Eurhinodelphinidae is a family of small- to moderate-size Late Oligocene to Miocene long-snouted odontocetes, including, among others, the genera Eurhinodelphis, Schizodelphis, Ziphiodelphis and Xiphiacetus. The only clear synapomorphy for the family is the edentulous premaxillae that extent far beyond the maxillae, getting the rostrum longer than the mandible. This specialized morphology of the feeding apparatus, combined with retention of a long neck, might suggest that these dolphins occupied a coastal or even estuarine habitat (Lambert, 2005a). Nevertheless, several species are known from both sides of the North Atlantic, a feature that contrasts with the seemingly endemic distribution of other species. Interestingly, members of the family where found in fresh water deposits from the Late Oligocene of southern Australia (Fordyce, 1983). Among other hypotheses, Eurhinodelphinidae have been phylogenetically located as the sister-group to Delphinida (Muizon, 1990; Fordyce, 1994). However, several similarities with beaked whales (Ziphiidae) (with respect to the morphology of the face, palate, and ear bones) suggest closer relationships with the latter (Lambert, 2005b). Muizon (1988) positioned the Italian Miocene long-beaked dolphin genus Eoplatanista (family Eoplatanistidae) as sister-group of the eurhinodelphinids and relationships within the family are investigated in Lambert (2005a).

- Kentriodontidae is a Late Oligocene to Late Miocene paraphyletic family whose ecological diversity has previously been underestimated (e.g., recently described large members of the family from the east coast of North America, Dawson, 1996a, b, long-snouted species from Portugal, Lambert et al. 2005), and from which extant delphinoids probably evolved. These archaic dolphins with numerous teeth were fish-eaters, like extant true dolphins. Similarities of the basicranium and sinus fossae with extant taxa indicate that kentriodontids already used echolocation for navigation and finding preys (Ichishima et al. 1994). The diagnosis of the family lacks well-defined synapomorphies, while the definition of the three known subfamilies Kentriodontinae (e.g., Delphinodon, the relatively cosmopolitan Kentriodon, Macrokentriodon, Rudicetus, Tagicetus), Pithanodelphininae (Atocetus, Pithanodelphis), and Lophocetinae (e.g., Hadrodelphis, Lophocetus) is somewhat better supported (discussion in Muizon, 1988; Ichishima et al. 1994; Dawson, 1996a,b; Bianucci, 2001; Lambert et al. 2005).

References

Bianucci, G. 2001. A new genus of kentriodontid (Cetacea: Odontoceti) from the Miocene of South Italy. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 21(3): 573-577.

Cassens, I., Vicario, S., Waddell, V. G., Balchowsky, H., Van Belle, D., Ding, W., Chen, F., Mohan, R. S. L., Simoes-Lopes, P. C., Bastida, R., Meyer, A., Stanhope, M. J., and Milinkovitch, M. C. 2000. Independant adaptation to riverine habitats allowed survival of ancient cetacean lineages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 (21): 11343-11347.

Cozzuol, M. A. 1985. Investigations on Cetacea 7: 39-53.

Cranford, T. W., M. Amundin, and K. S. Norris. 1996. Functional morphology and homology in the odontocete nasal complex: Implications for sound generation. Journal of Morphology 228:223-285.

Dawson, S. D. 1996a. A description of the skull and postcrania of Hadrodelphis calvertense Kellogg 1966, and its position within the Kentriodontidae (Cetacea; Delphinoidea). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16 (1): 125-134.

Dawson, S. D. 1996b. A new kentriodontid dolphin (Cetacea; Delphinoidea) from the Middle Miocene Choptank Formation, Maryland. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16 (1): 135-140.

Flower, W. F. 1869. Transactions of the Zoological Society, London 6: 87-116.

Fordyce, R. E. 1981. Systematics of the odontocete whale Agorophius pygmaeus and the family Agorophiidae (Mammalia: Cetacea). Journal of Paleontology 55(5): 1028-1045.

Fordyce, R. E. 1983. Rhabdosteid dolphins (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Middle Miocene, Lake Frome area, South Australia. Alcheringa 7:27-40.

Fordyce, R. E. 1994. Waipatia maerewhenua, new genus and new species (Waipatiidae, new family), an archaic late Oligocene dolphin from New Zealand. In : A. Berta and T. A. Deméré (eds.). Contributions in marine mammal paleontology honoring Whitmore, F.C. Jr. Proceedings of the San Diego Society of Natural History 29 :147-178.

Fordyce, R. E. 2002. Simocetus rayi (Odontoceti: Simocetidae) (new species, new genus, new family), a bizarre new archaic Oligocene dolphin from the eastern North Pacific. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 93: 185-222.

Gatesy, J., Milinkovitch, M. C., Waddell, V. and Stanhope, M. 1999. Stability of Cladistic Relationships between Cetacea and Higher Level Artiodactyl Taxa. Systematic Biology 48: 6-20.

Gray, J. E. 1863. Proceedings of the Zoological Society (London) 31: 197-202.

Hamilton, H., Caballero, S., Collins, A. G., and Brownell, R. L. Jr 2001. Evolution of river dolphins. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 268: 549-556.

Heyning, J. E. 1989. Comparative facial anatomy of beaked whales (Ziphiidae) and a systematic revision among the families of extant Odontoceti. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Contributions in Science 405:1-64.

Ichishima, H., Barnes, L. G., Fordyce, R. E., Kimura, M., and Bohaska, D. J. 1994. A review of kentriodontine dolphins (Cetacea; Delphinoidea; Kentriodontidae): systematics and biogeography. The Island Arc 3: 486-492.

Kasuya, T. 1973. Systematic consideration of recent toothed whales based on the morphology of tympano-periotic bone. Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute, Tokyo 25: 1-103.

Kellogg, R. 1928. The history of whales - their adaptation to life in the water. The Quarterly Review of Biology 3: 29-76, 174-208.

Lambert, O., 2005a. Review of the Miocene long-snouted dolphin Priscodelphinus cristatus du Bus, 1872 (Cetacea, Odontoceti) and phylogeny among eurhinodelphinids. Bulletin de l’Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, Sciences de la Terre, 75: 211-235.

Lambert, O., 2005b. Phylogenetic affinities of the long-snouted dolphin Eurhinodelphis (Cetacea, Odontoceti) from the Miocene of Antwerp. Palaeontology, 48 (3): 653-679.

Lambert, O., Estevens, M., and Smith, R., 2005. A new kentriodontine dolphin from the Middle Miocene of Portugal. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 50 (2): 239-248.

LeDuc, R. G., W. F. Perrin, and A. E. Dizon. 1999. Phylogenetic relationships among the delphinid cetaceans based on full cytochrome B sequences. Marine Mammal Science 15:619-648.

Luo, Z. & Gingerich, P. D. 1999. Terrestrial Mesonychia to aquatic Cetacea: transformation of the basicranium and evolution of hearing in whales. Papers on Paleontology, 31: 98 p.

Messenger, S. L. 1994. Proceedings of the San Diego Society of Natural History 29: 125-133.

Messenger, S. L. and J. A. McGuire. 1998. Morphology, molecules, and the phylogenetics of cetaceans. Systematic Biology 47:90-124.

Milinkovitch, M. C. 1995. Molecular phylogeny of cetaceans prompts revision of morphological transformations. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 10:328-334.

Milinkovitch, M. C., Ortí, G. and A. Meyer. Revised phylogeny of whales suggested by mitochondrial ribosomal DNA sequences.Nature, 361: 346-348 (1993).

Milinkovitch, M. C., A. Meyer, and J. R. Powell. 1994. Phylogeny of all major groups of cetaceans based on DNA sequences from three mitochondrial genes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 11:939-948.

Muizon, C. de 1985. Nouvelles données sur le diphylétisme des Dauphins de rivière (Odontoceti, Cetacea, Mammalia). C. r. hebd. Seanc. Acad. Sci., Paris, 301: 359-361.

Muizon, C. de 1987. The affinities of Notocetus vanbenedeni, an Early Miocene platanistoid (Cetacea Mammalia) from Patagonia, southern Argentina. American Museum Novitates 2904: 1-27.

Muizon, C. de 1988. Les relations phylogénétiques des Delphinida. Annales de Paléontologie 74 (4): 159-227.

Muizon, C. de 1991. A new Ziphiidae (Cetacea) from the Early Miocene of Washington State (USA) and phylogenetic analysis of the major groups of odontocetes. Bulletin du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris 4 C, (3-4): 279-326.

Muizon, C. de 1994. Proceedings of the San Diego Society of Natural History 29: 135-146.

Nikaido M., A.P. Rooney, and N. Okada. 1999. Phylogenetic relationships among cetartiodactyls based on insertions of short and long interpersed elements: Hippopotamuses are the closest extant relatives of whales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, pp. 10261–10266.

Nikaido, M., Matsuno, F., Hamilton, H., Brownel, R. L. Jr, Cao, Y., Ding, W., Zuoyan, Z., Shedlock, A. M., Fordyce, R. E., Hasegawa, M., and Okada, N. 2001. Retroposon analysis of major cetacean lineages: the monophyly of toothed whales and the paraphyly of river dolphins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98 (13): 7384-7389.

Pilleri, G. 1974. Investigations on Cetacea 4: 44-70.

Pilleri, G. and Gihr, M. 1980. Investigations on Cetacea 11: 33-36.

Rice, D. W. 1998. Marine mammals of the world. Systematics and distribution. Society for Marine Mammalogy, Special Publication, 4, Lawrence, Kansas, 231 p.

Rothausen, K. 1968. Die systematische Stellungsder europaischen Squalodontidae (Odontoceti, Mammalia). Palaeontologische Zeischrift 42: 83-104.

Zhou, K. 1982. Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute 34: 93-108.

Zhou, K., Qian, W., and Li, Y. 1979. Acta Zoologica Sinica 25: 58-74.

Information on the Internet

- The Firecracker Whale. A Compilation of Available Information on Kogia breviceps, the Pygmy Sperm Whale.

- The Twists in the Narwhal's Horn. Alaska Science Forum.

- Charlotte, The Vermont Whale. Website about a fossil beluga whale. University of Vermont.

- Saint Lawrence Belugas Program. Université de Montréal.

- The Dolphin Institute.

- Talamanca Dolphin Foundation.

- Dolphins: Oracles of the Sea. ThinkQuest Library.

- Dolphins. Hawaii's Marine Wildlife. Earthtrust, Kailua, Hawaii.

- Dolphins Around the World.

- Fundacion Orca Patagonia - Antártida. Observation program and study of behavior of orcas in the wild.

- OrcaLab. Long-term study of orcas in British Columbia, Canada.

- Killer Whale Biology. Eric Poncelet.

- Porpoise Science and Conservation.

Title Illustrations

| Scientific Name | Pseudorca crassidens |

|---|---|

| Location | Ecuador |

| Comments | False killer whales (Delphinidae) |

| Creator | Photograph by Gerald and Buff Corsi |

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Source Collection | CalPhotos |

| Copyright |

© 2001 California Academy of Sciences

|

About This Page

Michel C. Milinkovitch

Genetics & Evolution, University of Geneva

Olivier Lambert

Royal Institute of Natural Sciences (Belgium)

Correspondence regarding this page should be directed to Michel C. Milinkovitch at

Page copyright © 2012 Michel C. Milinkovitch and

All Rights Reserved.

- Content changed 30 January 2012

Citing this page:

Milinkovitch, Michel C. and Olivier Lambert. 2012. Odontoceti. Toothed whales. Version 30 January 2012 (under construction). http://tolweb.org/Odontoceti/16025/2012.01.30 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site