Taningia

Taningia danae

Michael Vecchione, Tsunemi Kubodera, and Richard E. YoungIntroduction

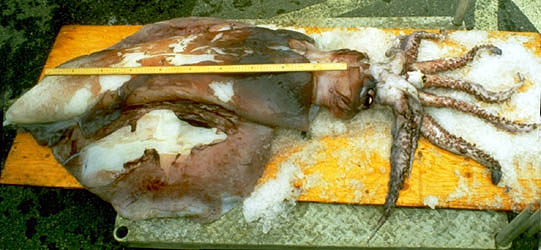

This species reaches a maximum of 170 cm ML (Nesis, 1981/87). In Taningia tentacles are reduced to minute appendages in young subadults and are absent in adults. The second arms carry large, lidded photophores at the arm tips.

Figure. Dorsolateral view of T. danae, 60 mm ML, Hawaiian waters. Photograph by R.Young.

Diagnosis

An octopoteuthid ...

- with large photophores at the tips of arms II; other arms without arm-tip photophores.

- without "tail" photophores.

Characteristics

- Tentacles

- Reduced to minute appendages in young subadults.

- Photophores

- Tips of Arms II modified into broad photophores with muscular lids.

Click on an image to view larger version & data in a new window

Click on an image to view larger version & data in a new window

Figure. Aboral views of a large arm II photophore of T. danae. Left - The arm tip photophore with the lids closed. Right - Double photographic exposure that shows the lids withdrawn revealing the white surface of the photophore overlaying a second exposure with the lids closed. Photographs by R. Young and C. Roper.

Comments

The visceral photophores are very hard to locate in preserved specimens.Behavior

Roper and Vecchione (1993) reported observations on bioluminescence in a 60 mm ML squid from Hawaiian waters. When disturbed, Taningia would attack and repeatedly flash the arm-tip photophores. The flash duration was generally only a fraction of a second; however on some occasions the arm tip glowed for periods of about 1-7 seconds. The aggressive flashing behavior is presumably used to startle predators via a mock attack. In addition, the visceral photophores were observed to glow for periods in excess of 15 min. and produced a general ventral glow. This latter behavior is suggestive of a counterillumination function (Roper and Vecchione, 1993). The photograph below left shows the squid on which these observations were made. The chromatophores are contracted on the midventral mantle skin which leaves a "window" for bioluminescent light from the viscera to emerge. The reflective photophores can be seen as a white streak. The photograph, below right, is from a different specimen that has the mantle cut open showing the visceral photophores.

Figure. Left - Ventral view of T. danae, 60 mm ML squid, Hawaiian waters. Right - Ventral view of visceral photophores of T. danae seen through a cut in the ventral mantle. Photographs by R. Young and C. Roper.

T. danae has been observed with a baited underwater camera in its natural habitat off the Ogasawara Islands in the western North Pacific (Kubodera, et al., 2006). The squid was photographed at depth of 240-940 m overall and at 614 and 940m depth at 0800 -0900 hrs, at 900 m at 1600 hrs, mainly at 500-600 m around sunset (1700-1900 hrs) and at 240-650 m at night (2000-2300 hrs). The squid swam using the large fins. Large amplitude waves in the fins passing from head to tail propelled the squid forward and reverse waves propelled it backwards.

Figure. Series of video frames of T. danae as it approached the bait showing the movement of the large fins. ©

On several occasions a squid of over 1 m total length was seen to actively attack the bait, attaining swimming speeds of 2-2.5 m/sec during the approach.

Figure. Video frames of T. danae attacking the bait. Left - Approaching the bait with arms spread. Middle - Swimming around the bait and catching it with arms IV. Right - Grabbing the bait with all arms just before swimming off. ©

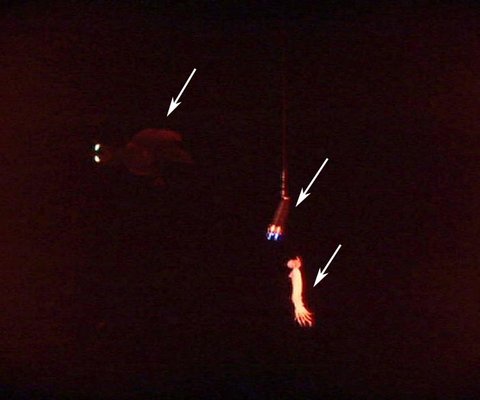

Insitu bioluminescence was also photographed by Kubodera, et al. (2006). The arm II photophores were seen to flash (< 2 seconds duration) as the squid attacked the bait with spread arms. The photophores were also seen to produce long-term glows (ca. 4-9 sec.) without attacking the bait, although swimming near the bait then extinguishing the light as the squid swam away. The function of the latter luminescence is uncertain. This behaviour was seen only when the two halogen lights adjacent to the camera were covered with red filters. Without the distracting large halogen lights visible, perhaps the squid interpreted the two dim lights hung above the bait as bioluminescence from another Taningia and its own glow was an attempt to communicate (e. g., "This is my prey") but without an appropriate response, the squid moved on (Kubodera, et al., 2006).

Figure. Video frame of T. danae producing a glow from its large arm II photophores (upper left arrow). The right bottom arrow points to the squid bait. The middle arrow points to two small lights attached near the bait which superficially appear similar in size and shape to the two squid photophores. The light and bait dangle on a line from a pole attached to the camera and large halogen lights that have been covered with a red filter during this sequence. ©

Life History

The paralarva is distinctive in having enlarged suckers on the thick tentacles and the tips of arms II swollen by the developing photophores.

Figure. Ventral view of the head of a paralarval T. danae, Hawaiian waters, mantle was misssing. Drawing by R. Young.

Figure. Dorsal and oral views of a paralarva of T. danae, Gulf of Aden, 4.7 mm ML. Drawings from Chun, 1910. This is the paralarva that Naef (1923) named Octopodoteuthopsis persica.

The juvenile T. danae (photographs below) can be quite translucent although the armtip photophores are heavily pigmented. The eyes are large, and the central brain and optic lobes (yellow) occupy a posterior position in the head, leaving a long anterior esophagus passing to the buccal mass.

Distribution

The type locality is off the Cape Verde Islands. The distribution includes the tropical and temperate regions of all oceans and boreal waters of the North Atlantic (Roper and Vecchione, 1993).

References

Chun, C. 1910. Die Cephalopoden. Oegopsida. Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Deutschen Tiefsee-Expedition, "Valdivia" 1898-1899, 18: 1-522 + Atlas.

Kubodera, T. , Y. Koyama and K. Mori. 2006. Observations of wild hunting behaviour and bioluminescence of a large deep-sea, eight-armed squid, Taningia danae. Proc. R. Soc. B, 2006.0236 . Published online.

Naef, A. (1921/23). Cephalopoda. Fauna und Flora des Golfes von Neapel. Monograph, no. 35. English translation: A. Mercado (1972). Israel Program for Scientific Translations Ltd., Jerusalem, Israel. 863pp., IPST Cat. No. 5110/1,2.

Nesis, K. N. 1982/87. Abridged key to the cephalopod mollusks of the world's ocean. 385+ii pp. Light and Food Industry Publishing House, Moscow. (In Russian.). Translated into English by B. S. Levitov, ed. by L. A. Burgess (1987), Cephalopods of the world. T. F. H. Publications, Neptune City, NJ, 351pp.

Roper, C. F. E. and M. Vecchione. 1993. A geographic and taxonomic review of Taningia danae Joubin, 1931 (Cephalopoda: Octopoteuthidae), with new records and observations on bioluminescence. P. 441-456. In:: T. Okutani, R. K. O'Dor and T. Kubodera (eds.). The Recent Advances in Cephalopod Fishery Biology. Tokai University Press. Tokyo.

Young, R. E. 1972. The systematics and areal distribution of pelagic cephalopods from the seas off Southern California. Smithson. Contr. Zool., 97: 1-159.

Information on the Internet

- Large squid lights up for attack. BBC News.

Title Illustrations

About This Page

National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D. C. , USA

Tsunemi Kubodera

National Science Museum, Tokyo, Japan

Richard E. Young

University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, USA

Page copyright © 1999 , , and Richard E. Young

Citing this page:

Vecchione, Michael, Kubodera, Tsunemi, and Young, Richard E. 2007. Taningia . Taningia danae . Version 29 April 2007. http://tolweb.org/Taningia_danae/19840/2007.04.29 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site