Hesionidae

Fredrik Pleijel and Greg W. Rouse

This tree diagram shows the relationships between several groups of organisms.

The root of the current tree connects the organisms featured in this tree to their containing group and the rest of the Tree of Life. The basal branching point in the tree represents the ancestor of the other groups in the tree. This ancestor diversified over time into several descendent subgroups, which are represented as internal nodes and terminal taxa to the right.

You can click on the root to travel down the Tree of Life all the way to the root of all Life, and you can click on the names of descendent subgroups to travel up the Tree of Life all the way to individual species.

For more information on ToL tree formatting, please see Interpreting the Tree or Classification. To learn more about phylogenetic trees, please visit our Phylogenetic Biology pages.

close boxIntroduction

The first described Hesionidae is Nereis punctata O. F. Müller 1776, now referred to Nereimyra; whereas hesionids as a family group were recognized for the first time by Grube (1850), then including Hesione, Psamathe and Nereimyra. Grube (1850) chose to base the family group name on Hesione, after the princess of Troy who was rescued by Hercules. Today there are 23 generic names in use, and c. 150 nominal species.

image info

image info

Figure 2. Undescribed hesionid from Lifou, Loyalty Islands. Copyright © 2000 Fredrik Pleijel.

All hesionids are benthic as adults and occur in marine environments only. They have a world-wide distribution in all seas, but are more common in shallow water and on continental shelves than in deep-water. A noteworthy exception is their presence at hydrothermal vents, cold-seep areas and on whale carcasses; eight species, some of which can appear in huge abundances, have been described from these habitats to date. Based on the few taxa that have been studied, it would appear that hesionids are active predators (see Pleijel, 2001 for references).

image info

image info

Figure 3. Gyptis sp., from shallow waters of South Australia. Copyright © 2004 Greg W. Rouse.

Characteristics

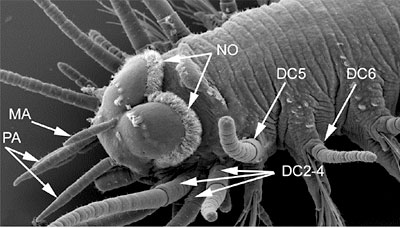

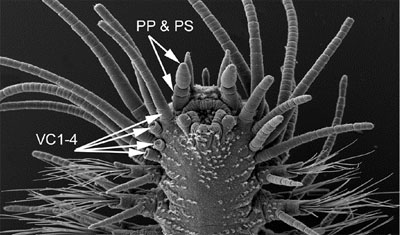

Synapomorphies for Hesionidae relate to the cephalisation of the first segments, and include the enlarged dorsal and ventral cirri and cirrophores on segment 1-5 and 1-3, respectively (Fig. 4) and absence of neurochaetae on segment 1-4 (Fig. 4; Pleijel, 1998). Although several of these features are reversed within the group, enlarged ventral cirri with well developed cirrophores on segment 1-3 are present in all hesionids and not outside this group.

image info

image info image info

image info

Figure 4. Gyptis sp. from South Australia. Top, anterior end in dorso-lateral view. Arrows indicate paired antennae (PA), median antenna (MA), nuchal organs (NO), dorsal cirri on segment 2-4 (DC2-4) (the dorsal cirri on segment 1 are hidden), and dorsal cirri on segment 5 (DC5) and 6 (DC6). Bottom, anterior end in ventral view. Arrows indicate the palpophore (PP) and palpostyle (PS) and the ventral cirri on segment 1-4. The ventral cirri on the right side of the animal are knocked off on segment 2-4, showing only the enlarged cirrophores; they are all entire on the left side. Copyright © 2004 Fredrik Pleijel.

Hesionids generally are provided with a pair of biarticulated palps, paired antennae, and, in some, a median antenna (Fig. 4). When present, there are two pairs of eyes. The proboscis is externally smooth in most taxa, but, as in many other Phyllodocida, it often ends with a ring of papillae (Fig. 5 right). A well-developed pair of lateral jaws occur in Nereimyra, Bonuania and Syllidia (Fig. 5 left) only (homologous with jaws in other Phyllodocida such as Nereididae and Chrysopetalidae), although several other taxa have a dorsal and/or a ventral tooth.

image info

image info  image info

image info

Figure 5. Left, jaws of Syllidia armata, Sweden. Right, Gyptis sp., South Australia, ventral view showing everted proboscis with a terminal ring of papillae. Both copyright © 2004 Fredrik Pleijel.

Usually, segments 1-4 or 1-5 show dorsal cirri and cirrophores that are larger and much longer than on the following segments (Fig. 6), and the same is the case for the ventral cirri on segment 1-3 or 1-4 (Fig. 4, 6). These segments also lack parapodial lobes and chaetae. Parapodia can have both simple noto- and compound neurochaetae, or compound neurochaetae only. They always carry dorsal and ventral cirri, and there is a single pair of pygidial cirri. External genital organs are usually absent, but have been reported for two members, Sinohesione and capricornia (see Westheide et al., 1994 and Pleijel and Rouse, 2000a, respectively). Most hesionids have separate sexes, although at least some members of Hesione are hermaphrodites.

image info

image info  image info

image info

Figure 6. Hesiospina aurantiaca, Papua New Guinea, anterior end in dorsal view, and Ophiodromus flexuosus, southern France, anterior end, ventral view, showing dorsal and ventral cirri and the first parapodium with chaetae on segments, left side. Copyright © 1997 Fredrik Pleijel.

Juvenile hesionids have a number of features that become modified in several different ways during development. Accordingly, all juveniles hitherto studied (members of Gyptis, Hesiospina, Micropodarke, Nereimyra, Ophiodromus, Podarkeopsis, and Psamathe; unpublished observations, but see also Haaland and Schram, 1982, 1983; Schram and Haaland, 1984) have a median antenna, situated medio-dorsally on the prostomium. In some taxa the median antenna remains dorsal during ontogeny, in some it migrates forward to the anterior margin of the prostomium (see Ophiodromus title illustration), and in others it becomes reduced (Figure 6 left). Another feature relates to the terminal proboscis ring. The distal end of the everted proboscis in juveniles has 10 papillae, whereas adult conditions vary from 10 papillae as in the juveniles to no papillae at all (i.e. reduced), or a varying but larger number of papillae (Fig. 5 right). Also, the anterior-most segments exhibit ontogenetic variation. Larvae lack chaetae and parapodia on segment 1, which is provided with dorsal and ventral cirri only, whereas the following segments have both parapodia and neurochaetae. As the animal grows, the chaetae and parapodia of these anterior-most segments are reduced on segments 3, 4 or 5, depending on the taxon. As these parapodial lobes are reduced, the dorsal and ventral cirri also become enlarged and prolonged.

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

Pleijel (1998), in a revision of Hesionidae, explored two approaches for rooting the tree. In one analysis, members of Chrysopetalidae and Nereididae were used, whereas in another it was rooted with an "ontogenetic outgroup", scored with states appearing early in the ontogeny of hesionids. The former analysis yielded the topology in the tree above (Fig. 1, with the addition of some recently described taxa), whereas the latter retained the clades Ophiodrominae, Gyptini, Ophiodromini, and Hesionini unaltered, but with Hesioninae and Psamathini appearing as basal grades. Since the ontogenetic data were obviously more incomplete, the results from the former analysis were used for classifying the hesionids, but it should be kept in mind that the root position requires further attention.

Licher and Westheide (1994) suggested that Pilargidae actually may be nested within Hesionidae. This was rebutted by Pleijel and Dahlgren (1998) and Dahlgren et al. (2000), who in the former study also removed the two interstitial groups Microphthalmus and Hesionides from Hesionidae. These taxa are currently referred to as Nereidiformia incertae sedis and not included in the Hesionidae clade.

Classification

The hesionid revision by Pleijel (1998) includes both traditional Linnaean names, and phylogenetic definitions (e.g. Cantino and de Queiroz, 2000) of a number of the names of the more inclusive clades. Phylogenetic nomenclature, without Linnaean names, was fully applied in a revision of Heteropodarke (Pleijel, 1999). This study also included a critique of the use of species concepts in taxonomy, and presented a system where clades only—and not species—are recognized. These phylogenetic names, however, are purely "experimental" at this stage; they are not established in the sense of the PhyloCode (Cantino and de Queiroz, 2000) that will be active from 1 January 2005 and will not be retroactive.

Pleijel and Rouse in two studies (2000a; 2000b) further explored problems with the species issue and introduced the LITU (Least Inclusive Taxonomic Unit) concept, i.e. the smallest clades which currently have been recognized. This was applied in a case study that introduced the new hesionid taxon capricornia, and is further discussed on that page.

| Hesionidae | |||||

| Ophiodrominae | |||||

| Gyptini | |||||

| Amphiduros Amphiduropsis Gyptis capricornia Hesiodeira Parahesione |

|||||

| Ophiodromini | |||||

| Mahesia Heteropodarke Parasyllidea Ophiodromus Sinohesione Podarkeopsis |

|||||

| Hesioninae | |||||

| Psamathini | |||||

| Bonuania Hesiospina Micropodarke Nereimyra Psamathe Sirsoe Syllidia |

|||||

| Hesionini | |||||

| Hesione Leocrates Leocratides Wesenbergia |

|||||

| Hesiolyrinae | |||||

| Hesiolyra | |||||

References

Cantino, P.D., and de Queiroz, K. 2000. PhyloCode: A Phylogenetic Code of Biological Nomenclature. http://www.ohiou.edu/phylocode.

Dahlgren, T.G., Lundberg, J., Pleijel, F., and Sundberg, P. 2000. Morphological and molecular evidence of the phylogeny of Nereidiform polychaetes (Annelida). J. zool. Syst. evol. Res. 38:249-253.

Grube, A.E. 1850. Die Familien der Anneliden. Arch. Naturgesch. 16:249-364.

Haaland, B., and Schram, T.A. 1982. Larval development and metamorphosis of Gyptis rosea (Malm) (Hesionidae, Polychaeta). Sarsia 67:107-118.

Haaland, B., and Schram, T.A. 1983. Larval development and metamorphosis of Ophiodromus flexuosus (Delle Chiaje) (Hesionidae, Polychaeta). Sarsia 68:85-96.

Licher, F., and Westheide, W. 1994. The phylogenetic position of the Pilargidae with a cladistic analysis of the taxon—facts and ideas. In: J.-C. Dauvin, L. Laubier and D. J. Reish (Eds), Actes de la 4ème Conférence internationale des Polychètes, Mémoires du Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle. pp. 223-235.

Pleijel, F. 1998. Phylogeny and classification of Hesionidae (Polychaeta). Zool. Scr. 27:89-163.

Pleijel, F. 1999. Phylogenetic taxonomy, a farewell to species, and a revision of Heteropodarke (Annelida, Polychaeta, Hesionidae). Syst. Biol. 48:755-789.

Pleijel, F. 2001. 18. Hesionidae Grube, 1850. In: G. W. Rouse and F. Pleijel, Polychaetes, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 91-93.

Pleijel, F., and Dahlgren, T.G. 1998. Position and delineation of Chrysopetalidae and Hesionidae (Annelida, Polychaeta, Phyllodocida). Cladistics 14:129-150.

Pleijel, F., and Rouse, G.W. 2000a. A new taxon, capricornia (Hesionidae, Polychaeta), illustrating the LITU ("Least Inclusive Taxonomic Unit") concept. Zool. Scr. 29:157-168.

Pleijel, F., and Rouse, G.W. 2000b. Least-inclusive taxonomic unit: a new taxonomic concept for biology. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B. 267:627-630.

Schram, T.A., and Haaland, B. 1984. Larval development and metamorphosis of Nereimyra punctata (O.F. Müller) (Hesionidae: Polychaeta). Sarsia 69:169-181.

Westheide, W., Purschke, G., and Mangerich, W. 1994. Sinohesione genitaliphora gen. et sp. n. (Polychaeta, Hesionidae), an interstitial annelid with unique dimorphous external genital organs. Zool. Scr. 23:95-105.

Title Illustrations

| Scientific Name | Amphiduros fuscescens |

|---|---|

| Location | Canary Islands |

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Copyright | © 2001 Leopoldo Moro |

About This Page

Thanks to Leopoldo Moro for permission to use the beautiful picture of Amphiduros fuscescens.

Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, 57, rue Cuvier 75231 Paris, France

South Australian Museum, Nth Terrace, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia

Correspondence regarding this page should be directed to Fredrik Pleijel at and Greg W. Rouse at

Page copyright © 2004 and

- First online 13 April 2004

- Content changed 13 April 2004

Citing this page:

Pleijel, Fredrik and Rouse, Greg W. 2004. Hesionidae. Version 13 April 2004 (complete). http://tolweb.org/Hesionidae/22789/2004.04.13 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/